Weekly briefing

ACA

What to do with the ACA enhanced subsidies?

There really isn’t much of an update here. The government is still shut down, and the asks from the Democrats and the responses from Republican leadership are still largely the same.

But I said last week that you can start to see the shape of the deal, and if you squint, that shape is becoming a bit more defined.

A quick reminder on the arithmetic: the Continuing Resolution from the House needs four more Democratic votes in the Senate to break the filibuster.

Despite insisting they won’t negotiate on the subject until the government reopens, Republicans are floating some test balloons, and Majority Leader John Thune is “dangling” the promise of a vote after the government reopens, which is at least a little bit of negotiating.

As we’ve discussed, the damage to the risk pools is probably baked in already, along with the price increases. If you’re a payer or provider, none of this really changes your approach to 2026 and what it will look like in terms of MLR and uncompensated care.

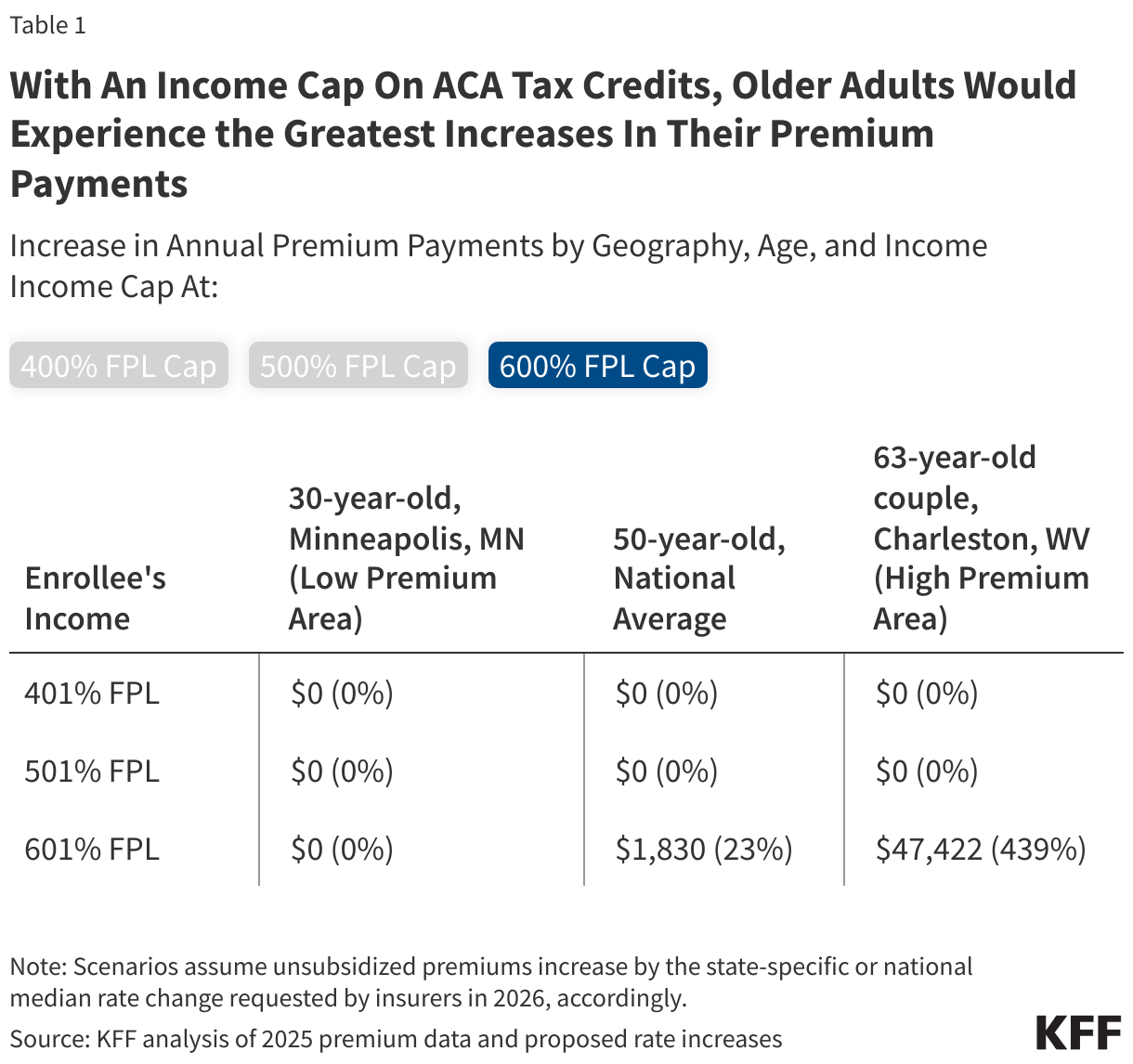

The promise of a vote, some reasonable-sounding demands which I’ll discuss further below, and the widespread public support for fixing this, at least for next year, might give at least 4 Democrats enough confidence to reopen the government.

Analysis

I’m not going to make a prediction here or do political analysis because I don’t have much value to add there. But I do want to talk about the Republican proposals on their merits:

(1) Income limits for the subsidies on the order of $200k.

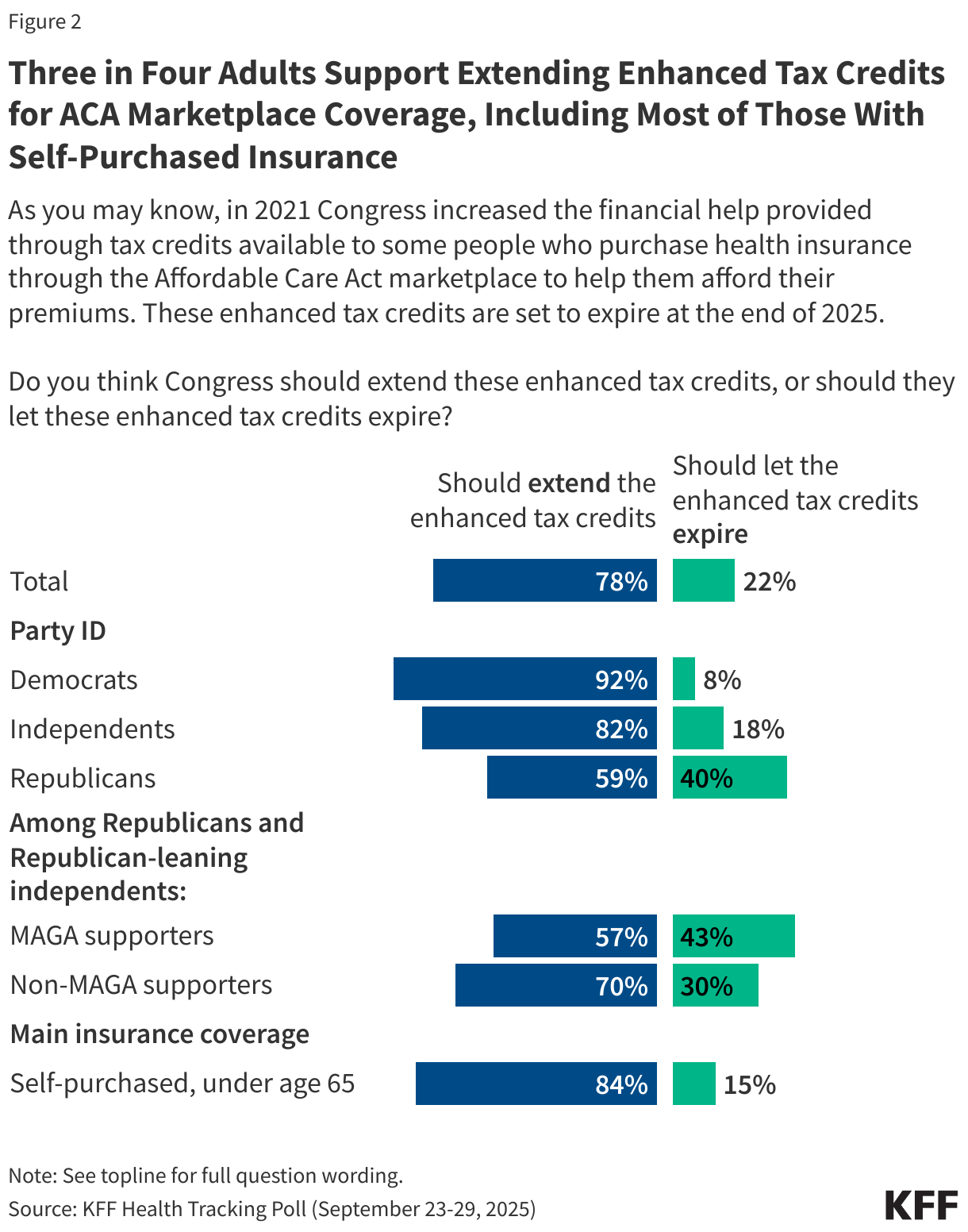

KFF put together this helpful quick take on what income caps could look like at 400%, 500%, and 600% of the federal poverty line, and there’s a scenario where a hypothetical 63-year-old couple in Charleston, WV is spending an extra $47k a year on premiums.

That’s a lot of money! But $200k is a lot higher than 600% of the FPL for all but a family of four. So I think the hypothetical 63-year-old couple in Charleston, WV will probably be okay.

1 person: ≈1,278% FPL (200,000 ÷ 15,650)

2 people: ≈945.6% FPL (200,000 ÷ 21,150)

3 people: ≈750.5% FPL (200,000 ÷ 26,650)

4 people: ≈622.1% FPL (200,000 ÷ 32,150)

(2) Minimum out-of-pocket premiums

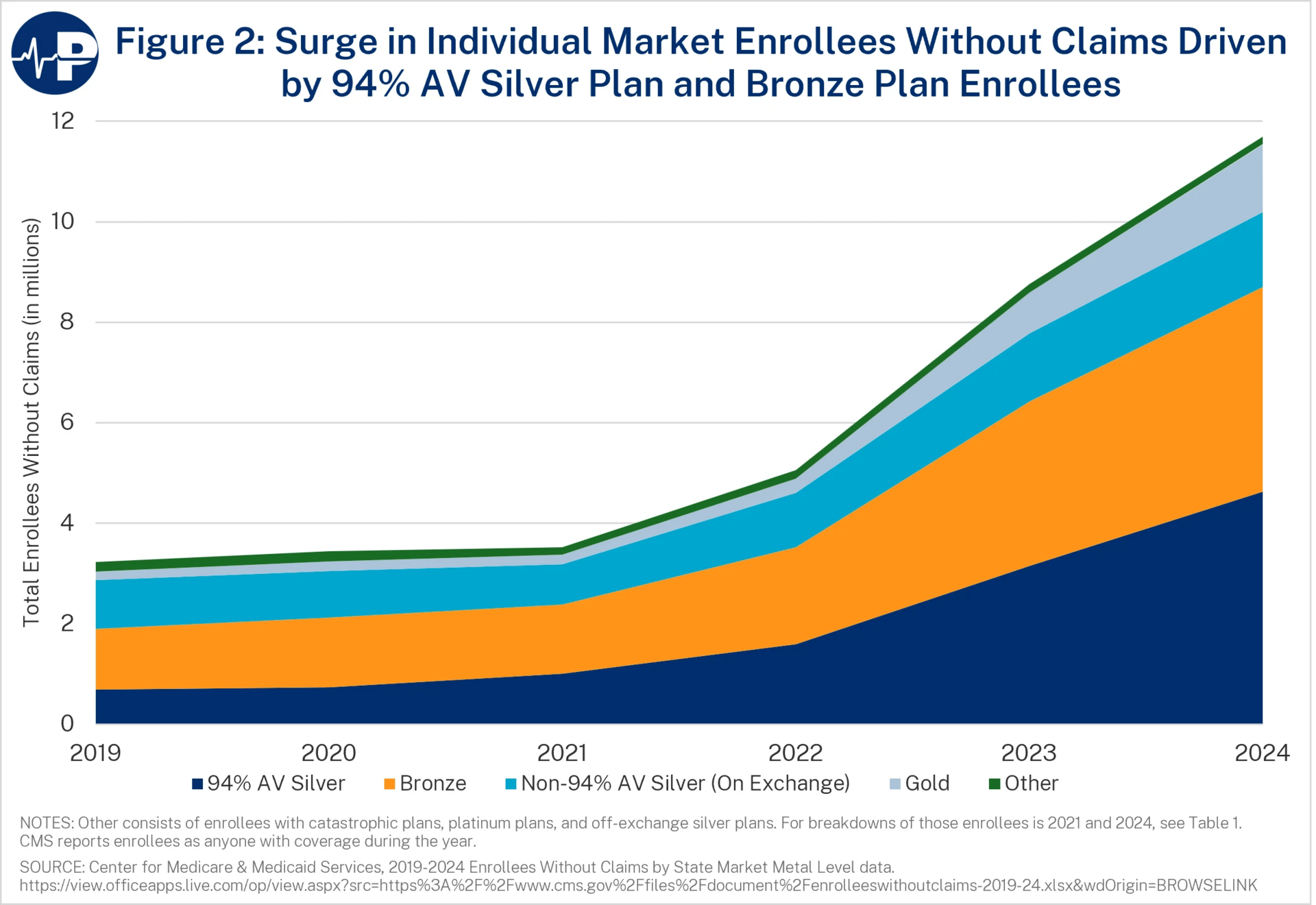

There are legitimate concerns about zero-dollar premium plans driving fraud in the ACA market, a concern the conservative Paragon Institute has done much to document. The main measure Paragon is using to track this is “zero-claim enrollees,” and the idea is that if you don’t have to pay a premium, brokers and payers might sign you up without you knowing. They’ll get paid, you won’t even know you had insurance because it’s free, and everyone is better off except the taxpayer.

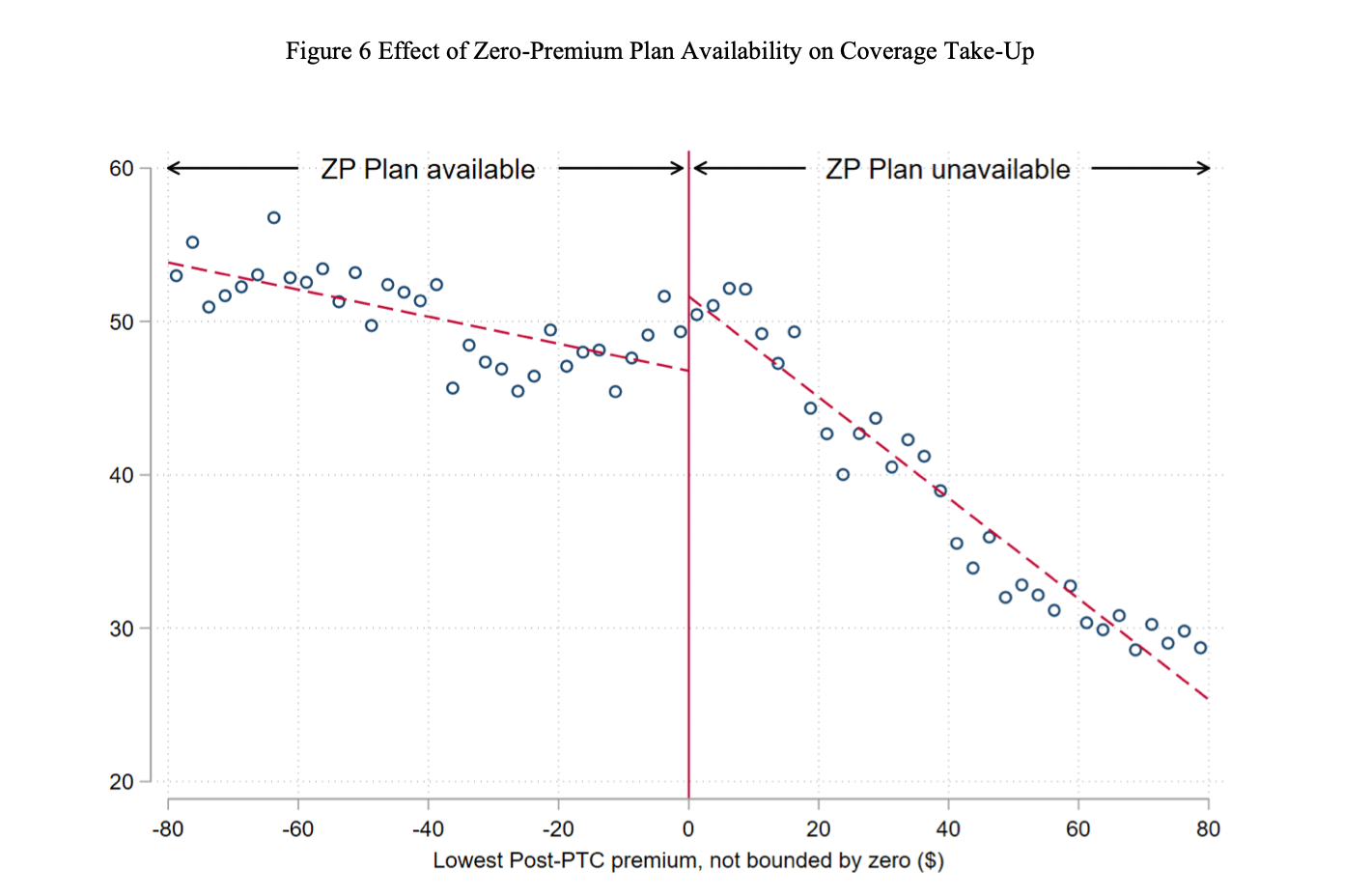

The pushback on this, articulated by the Families USA advocacy group in this comment letter, is that basically zero-dollar premiums are really nice for low-income people. There’s a great paper from Coleman Drake, Sih-Ting Cai, David Anderson, Daniel W. Sacks called Financial Transaction Costs Reduce Benefit Take-Up: Evidence from Zero-Premium Health Insurance Plans in Colorado.

Which, obviously! Zero is a special price. The question here is about the optimal level of fraud— Paragon thinks the status quo is too high, Families USA thinks it’s just right.

(3) Cutting off enhanced tax credits for new enrollees

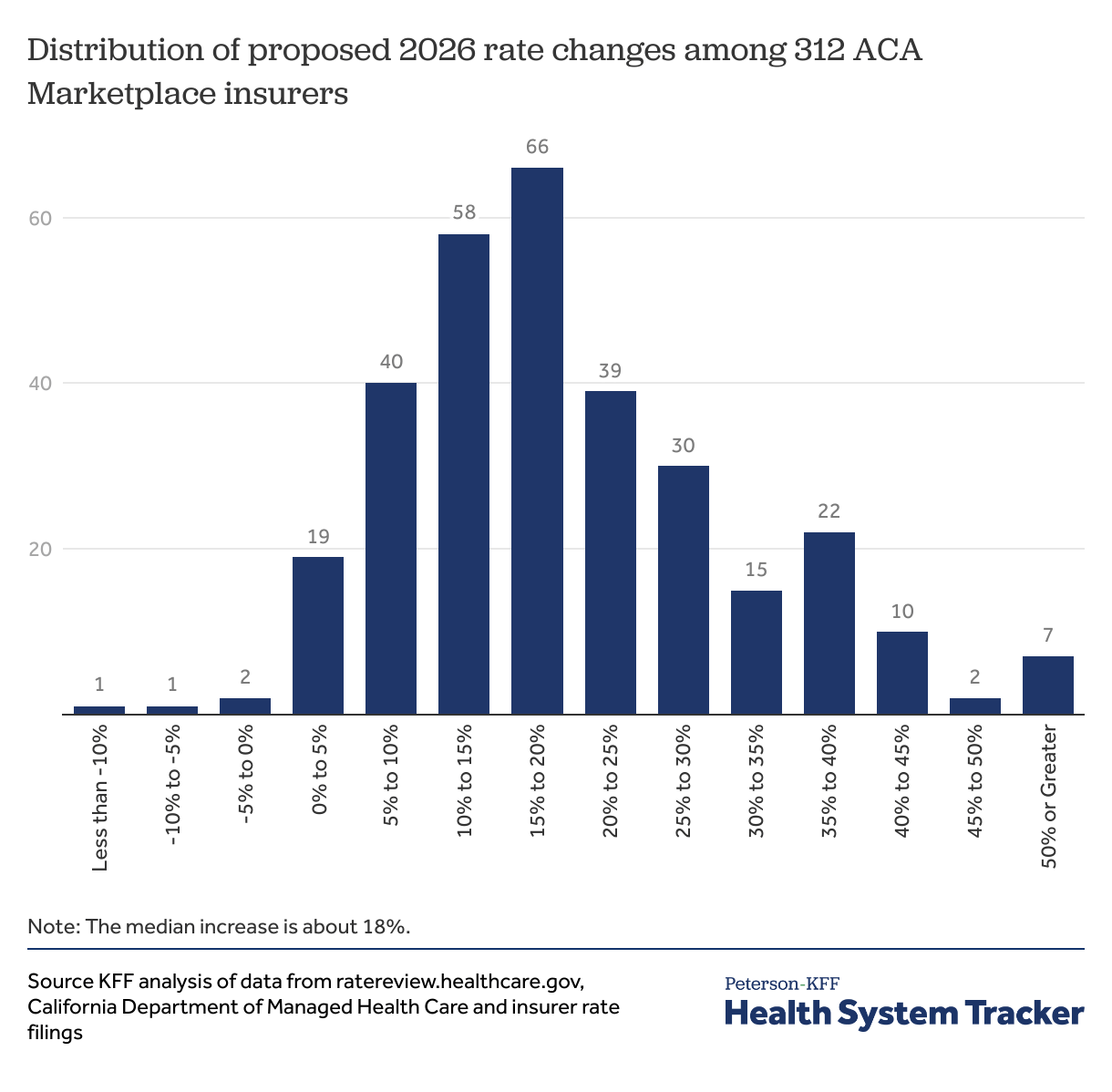

This one is pretty straightforward: you grandfather in re-enrollees, but new enrollees for 2026 don’t get the enhanced subsidies. It would save some money, but with premiums already up quite a bit year over yea,r including partly due to the expiration of the enhanced subsidies, there will be some sticker shock for new enrollees.

There’s always the chance there will be more comprehensive overhauls with “some GOP hard-liners are again embracing repeal-and-replace rhetoric,” but hopefully nothing major for the 2026 open enrollment seaso,n which starts in most states in 14 days.

Medicaid

Senatorial scrutiny for Deloitte and its Medicaid business

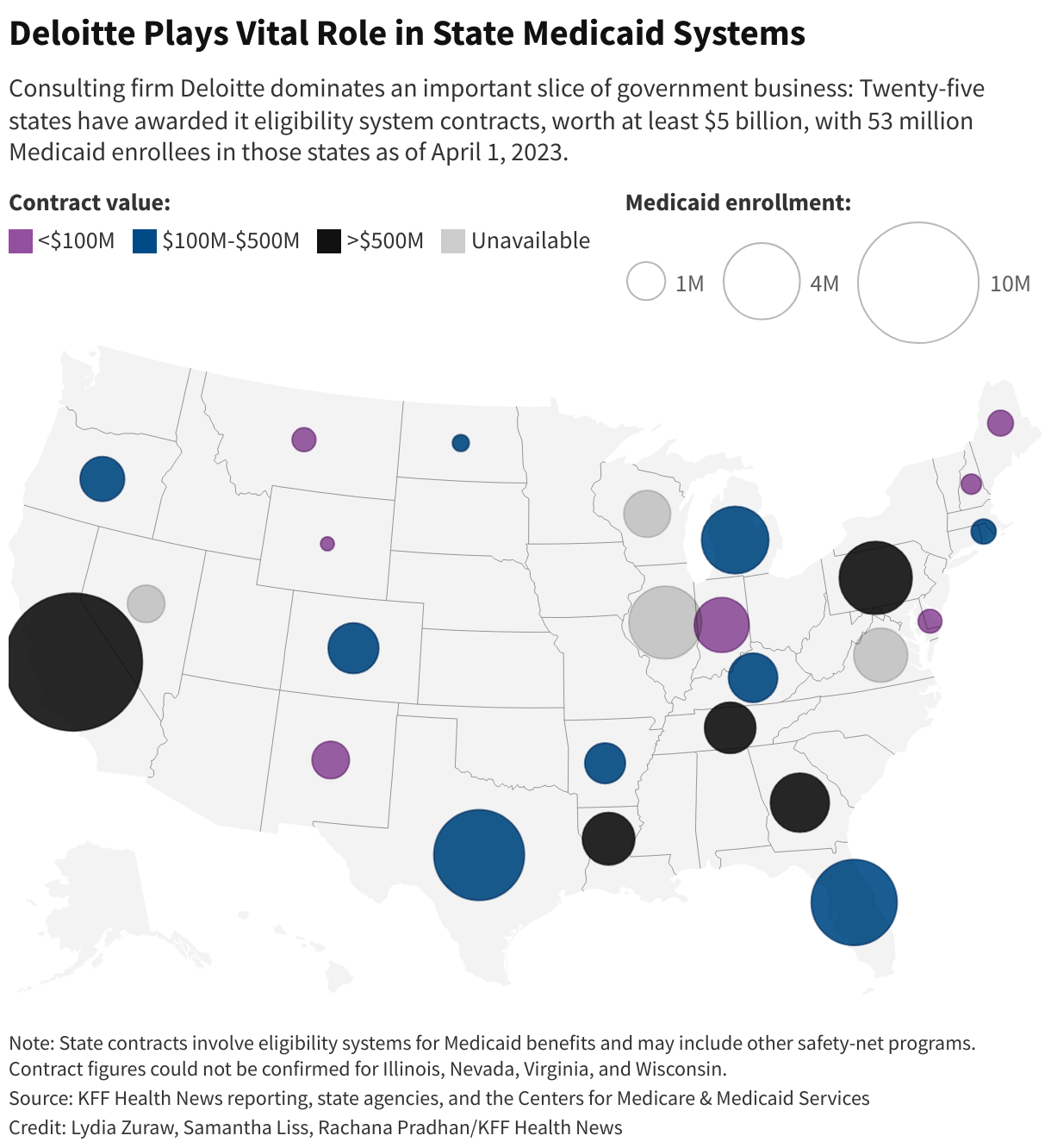

The consultancy Deloitte is a major provider of the infrastructure for state Medicaid agencies with approximately $6 billion worth of contracts to manage eligibility and enrollment:

There’s been some major issues with these systems, including delays, improper denials, and errors resulting in some pretty bad outcomes, like, for example, cutting off new moms from their coverage in Florida. In any case, this would be a cause for concern, but with the looming implementation of the One Big Beautiful’s new Medicaid requirements, it’s an even more salient issue.

Senators Wyden, Warren, Warnock, and Sanders sent a letter with questions to Deloitte along with other eligibility and enrollment vendors, including Gainwell Technologies, and Conduent last Friday. I expect we’ll be seeing a lot more scrutiny of these vendors as the Big Beautiful Bill adds complexity and increases the volume of redeterminations.

Analysis

Eligibility and enrollment is the whole ball game for Medicaid over the next few years. I personally don’t have a lot of optimism that Deloitte and its state partners are going to get drastically better at this by 2027. To be fair, it’s a hard, multi-faceted problem on a massive scale, but on the other hand, I think there are a lot of people in the Health Tech Nerds community who would be able to solve it for $6 billion dollars.

One of those people is Nikita Singareddy, cofounder and CEO of Fortuna Health. We interviewed her earlier this year, shortly after the OBBBA passed, and I recently wrote a report on their busines,s which you can read here.

In some ways, it’s frustrating that we need an additional, private, venture-backed layer on top of the systems built by Deloitte and its peers. But as a business opportunity, to quote Dan Davies on a different subject, “don’t underestimate simple inertia, incompetence and general failure to get one’s act together, which are often the most powerful competitive forces…”

Medicare

Confusion about the claims hold for Medicare

To a first approximation, the way traditional Medicare works for providers is that when they perform a service, they send a bill to their Medicare Administrative Contractor or MAC, which processes the claim. The government pays for it, but the government contracts out a lot of stuff, and evaluating and paying claims for Medicare fee-for-service is one of those things.

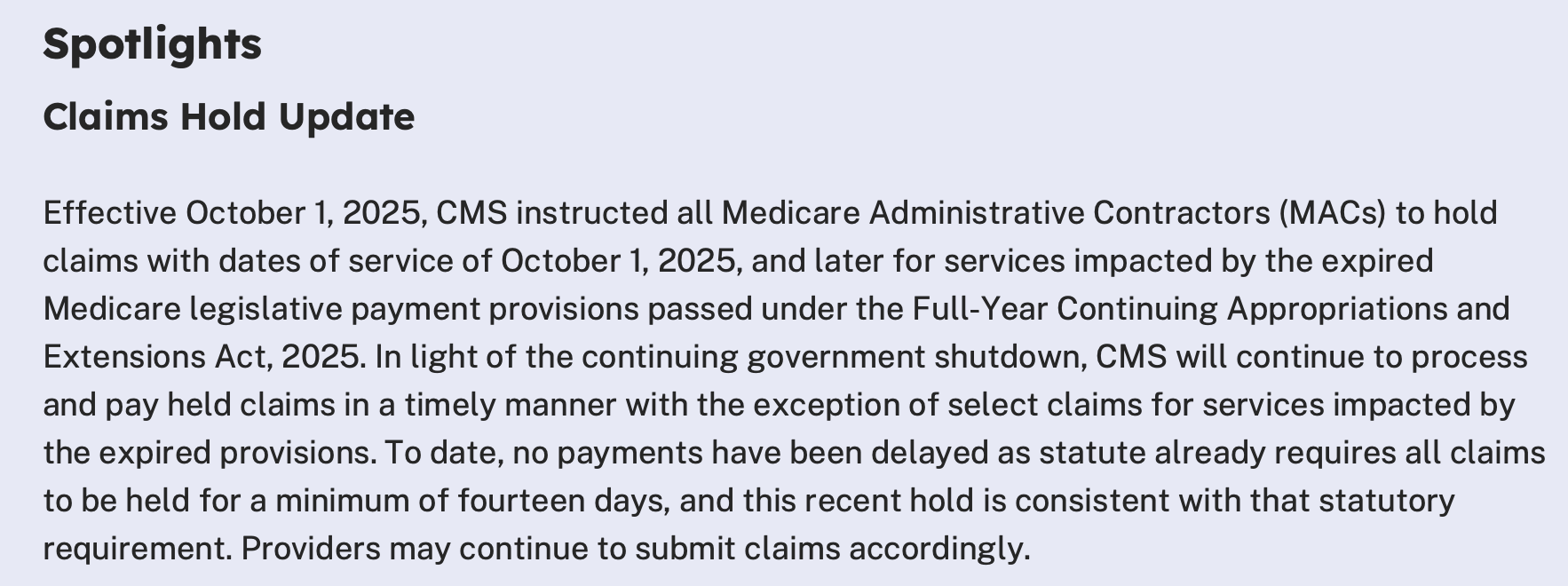

The MACs have a 14 day claim floor and 30 day claims ceiling, meaning they will pay the claim between 14 and 30 days after a claim is submitted; otherwise, they owe interest. Sometimes, CMS asks them to hold on to claims when there’s a potential change afoot.

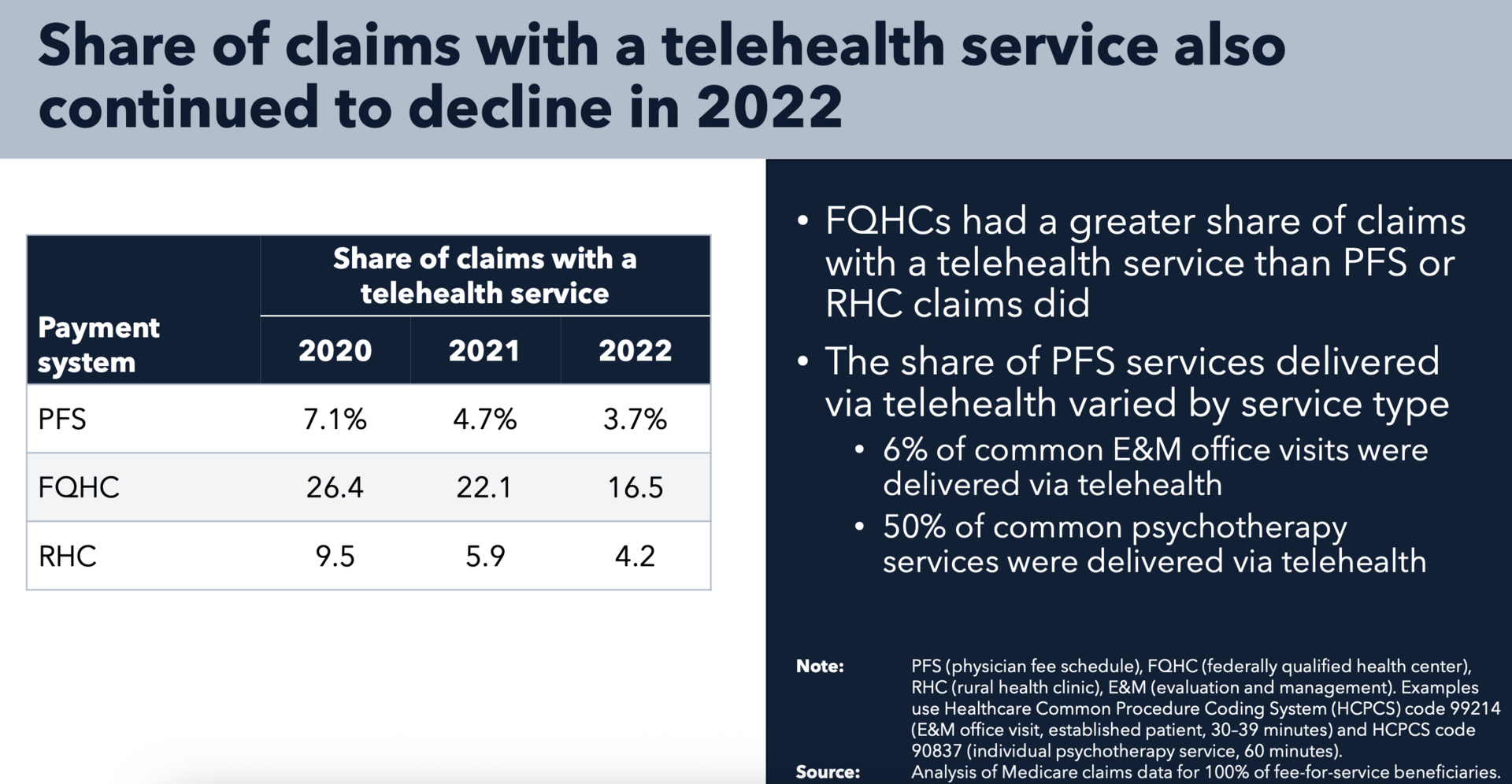

Medicare’s telehealth flexibilities expired at the end of September. Congress has to renew them every year until they decide whether they want to make them permanent, and they usually do that as part of the budget. When they finally do pass a budget, CMS expects them to extend the telehealth flexibilities, so CMS is asking the MACs to hold off on paying telehealth claims right now with a service date of October 1st or later. Legally, these claims should just be rejected— you mostly can’t do telehealth right now because the flexibility has expired. But CMS would rather not have to have everyone reprocess all the claims in the case that Congress does what everyone is expecting it to do and extends the flexibilities.

Telehealth is not a huge part of Medicare, but it’s not trivial, either, so you can see why they would want to wait for clarity from Congress before running all the claims.

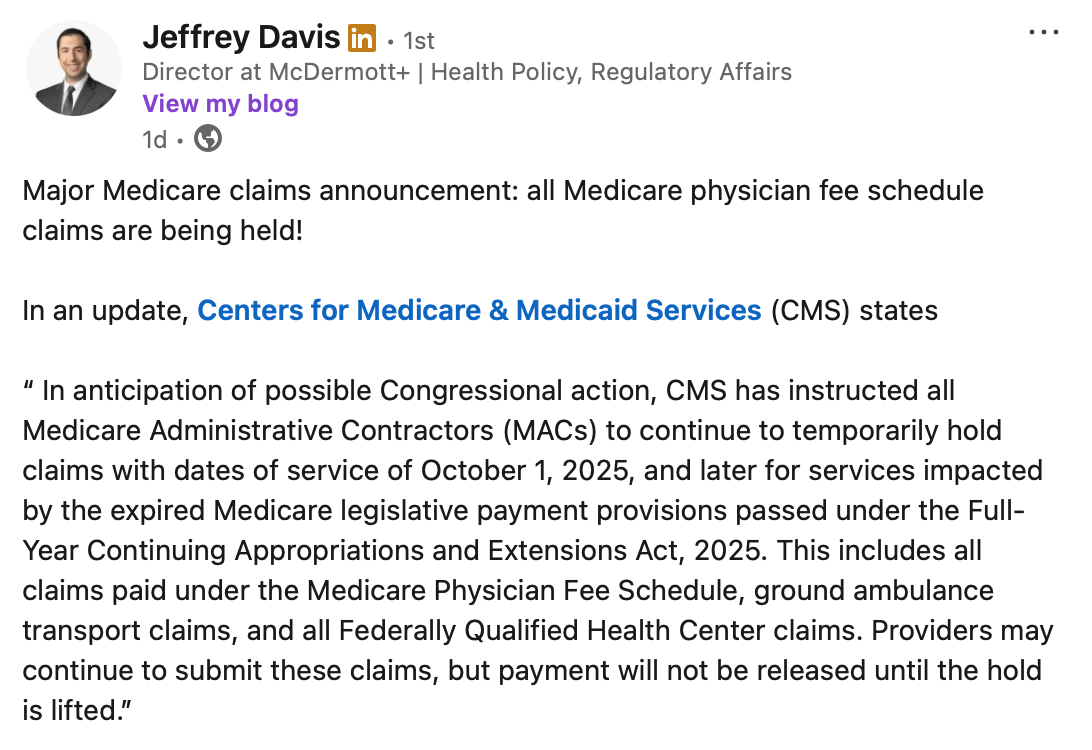

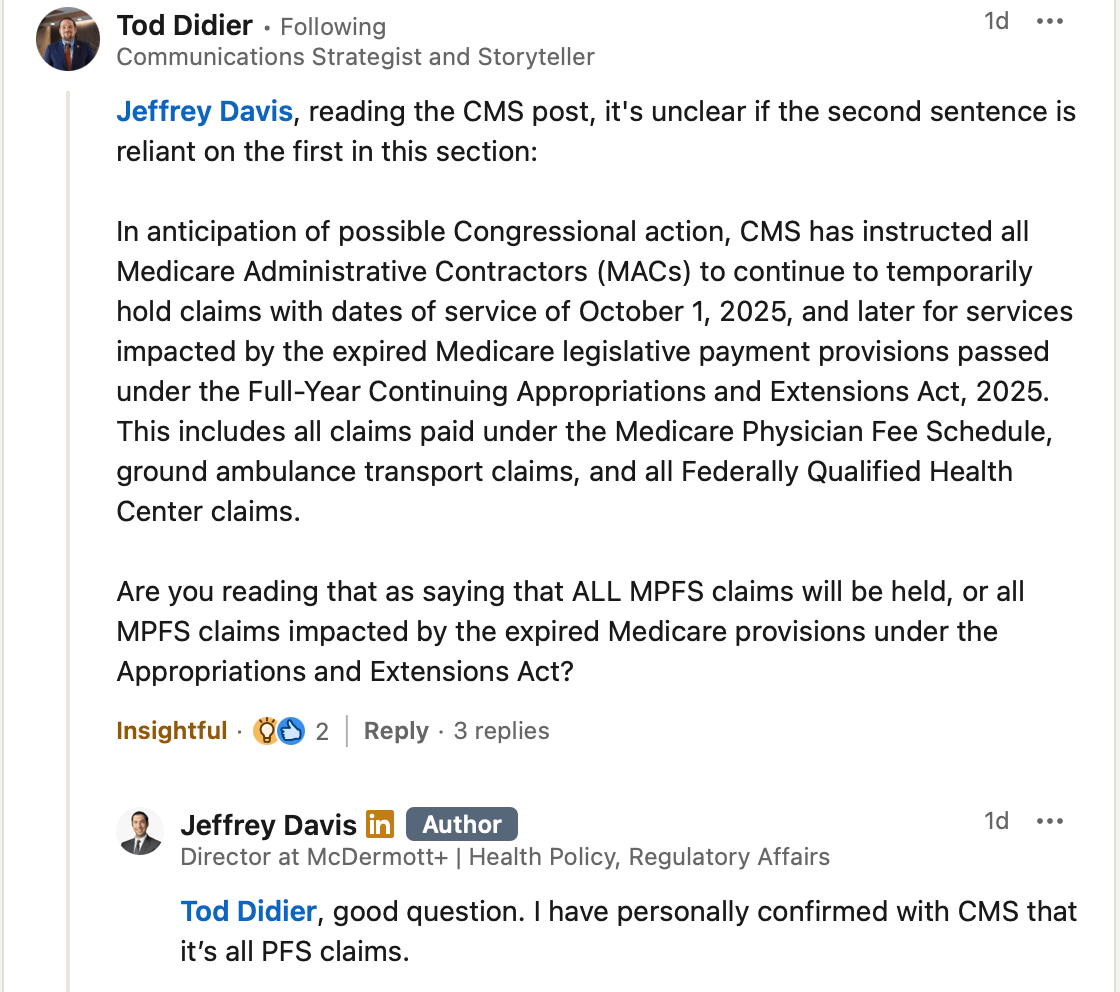

But for about 12 hours between Wednesday afternoon and Thursday morning, there was some confusion about whether it was just the telehealth claims or all Physician Fee Schedule claims, with Jeffrey Davis of McDermott+ sharing:

I did some back-of-the-envelope math, and very roughly, a day’s worth of Physician Fee Schedule claims, with no adjustments for seasonality or weekend/weekdays, is ~$700 million1. Given the size of this figure, people were incredulous. But Jeffrey Davis spoke with someone at CMS, and they confirmed: all PFS claims, all $700 million per day.

This turned out not to be the case, and whoever spoke with Jeffrey at CMS no doubt got an awkward tap on the shoulder. The language was updated by the following morning. CMS clarified that it was just the telehealth claims being held:

Analysis

I don’t have a good sense of the typical provider group’s cash situation. In my personal experience, I’ve noted that some providers bill my insurance immediately, and others take their sweet time. I assume the ones that bill my insurance immediately need the money more than the ones who wait months or even almost a year. Regardless, I feel comfortable asserting that pulling an additional $700 million per day out of provider pockets would be disruptive, so I’m happy that got sorted out.

Quick Hits

Medicaid-focused maternal health company Ouma Health acquired four brick and mortar maternal-fetal medicine clinics across Florida, Massachusetts, and Maine, expanding from exclusively telemedicine to a hybrid model.

Town Hall Ventures, a venture capital fund focused on underserved communities in healthcare, announced a $440 million Fund IV. My colleague Kevin interviewed General Partner Meera Mani this morning, and you can watch a reply here.

A Health Affairs article found that decreased concentration in Medicare Advantage markets led to most improvements in market outcomes

In Acute Condition, Olivia Kosloff revisited the strange case of MultiPlan and its postmodern antitrust implications

Dr. Oz ponders the potential of Medicare Advantage: “MA is still in its infancy. It’s walking, but can it run? Can it fly?” at the Better Medicare Alliance MA Leadership & Policy Forum

Long form: There are different prices for the same thing

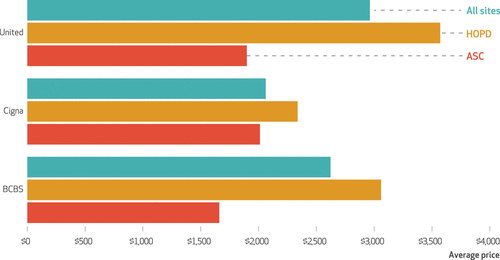

A strange quirk of the US healthcare is that there are a lot of different prices what is ostensibly the same service. For instance, insurance companies pay more for the same procedures at hospital outpatient departments than at ambulatory surgery centers, according to this Health Affairs article:

Payers and patients find it maddening. Economists and MBA graduates mumble about the law of one price. And policymakers talk about site-neutral payments as an easy and obvious reform for Medicare.

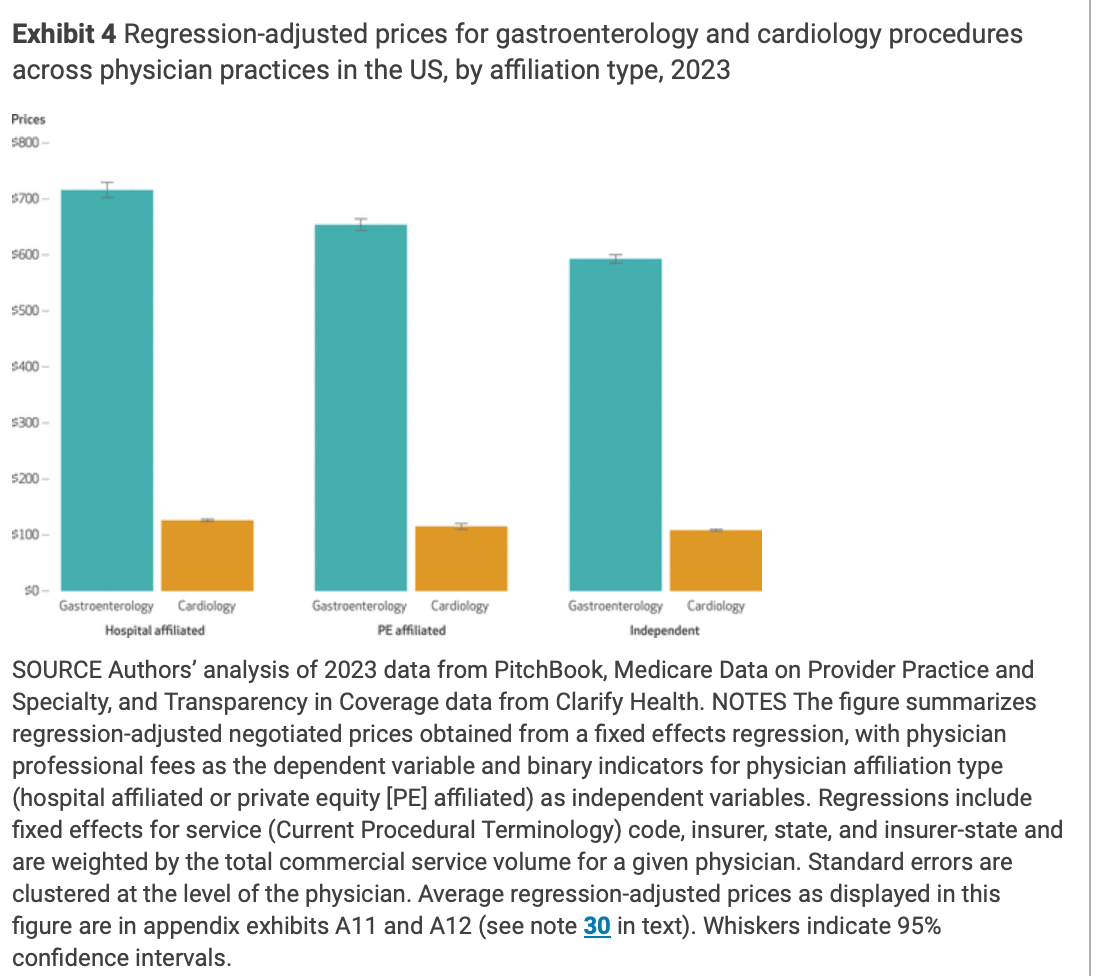

Another context where this comes up a lot is in the context of practice ownership. Health Affairs had another article this month showing different prices based on the economic owner of the clinic:

If you want the best price for your gastro or cardiology procedure, an independent clinic is your best bet. On the one hand, this isn’t all that surprising. On the other hand, it’s sure to add fuel to the corporate practice of medicine debate fire that is ever-burning.

I’m sympathetic to the view that the health care system would be better and cheaper if all practices were independent. But I do think it’s worth thinking through the trade-offs thoroughly before we try to operationalize this feeling. The analogy that’s been knocking around my head is landlords. There are independent landlords and there are corporate or professional landlords. With an independent landlord, there’s a chance you can get below market prices on your rent because they aren’t as savvy or just aren’t as interested in maximizing profits. With a corporate landlord, you can be pretty sure that what you’re paying is the highest rate the market will bear.

But you might have other preferences that come into play. The independent landlord might give you a good price, but is more likely to defer maintenance or be slow to get things repaired. The professional landlord is an easier and more finable target for city inspectors, so they might be more incentivized to make sure everything is up to code.

All in all, price is just one part of the offering. Quality, access, and cash reserves to weather shocks are other factors that might have social utility. This is true for landlords and for clinics— there’s probably greater variation on price, but also on all the other things for independents versus hospital and PE-affiliated practices.

Professional management makes things more expensive. According to the Health Affairs article, it’s a 6-10% premium. But it’s not too hard to imagine a clogged toilet after midnight type situation where you’d prefer the professional management over a more mom and pop approach.

1 Medicare spending on Physicians and Clinics is $255 billion per annum, divided by 365. Don’t take this number too seriously, but it’s probably the right order of magnitude.