Weekly Briefing

ACA

No deal, but some ideas for what to do about the expiring enhanced premium tax credits

As a condition of voting to reopen the government, Senate Democrats got a promise for a vote on extending the Affordable Care Act enhanced advance premium tax credits (eAPTCs).

Two weeks into open enrollment, the fate of the eAPTCs is still in question. It seems like there are probably 218 votes in the House for extending them in some form, but short of a heavy procedural lift, there is no real way to get a bill to the floor and Senate Republicans are throwing around alternatives that constitute a pretty material change to the program.

The basic shape of the idea comes from the Paragon Institute’s “The HSA Option” paper, with different flavors of the proposal coming from Bill Cassidy, Republican Senator from Louisiana and chair of the Senate health committee that involves FSAs and the President himself that would deliver direct cash payments in lieu of insurance subsidies.

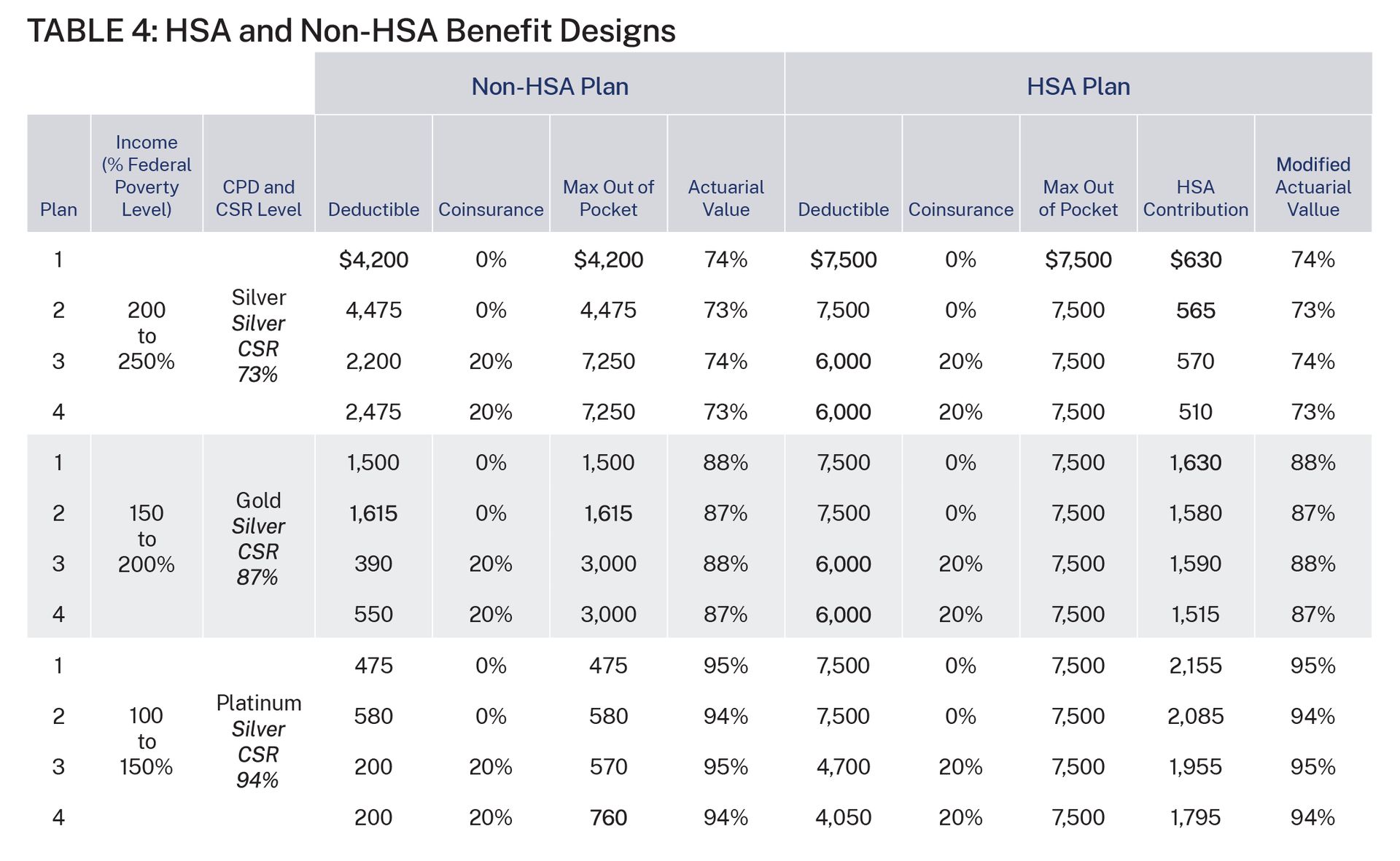

There’s a definite appeal to the HSA option. It prohibits “silver loading”, funds Cost Sharing Reduction payments to insurers, and requires exchange insurers to offer plans with higher deductibles and co-pays than the law currently requires, but also a contribution to a participant’s HSA account:

It would save money compared to both the expiration scenario and the extension scenario because funding Cost Sharing Reductions and disallowing silver loading are a good deal for the government relative to the inflated, silver-loaded subsidies.

Analysis

I am predisposed to liking something like the HSA option from Paragon because it’s vaguely Singaporean, and I read Lee Kuan Yew’s From Third World to First and swallowed it whole.

But these proposals, whether the Paragon option, the FSA option, or the direct cash option, all represent very fundamental changes to the individual market and, I must emphasize again, we are two weeks into open enrollment and the products are already designed and priced based on a set of assumptions including that the enhanced subsidies are expiring and that the structure of the program isn’t radically changing.

If the government tries to do something this year, it could disrupt the market in pretty significant ways. Cash transfers, or HSA or FSA contributions, in lieu of insurance subsidies would fundamentally change the risk pool as you take money that’s only useful for buying insurance and turn it into money that merely could be used to pay insurance premiums in the case of cash, or mostly can’t be used to buy insurance in the case of HSAs and FSAs. Unlike letting the enhanced premium tax credits expire, this could actually cause a death spiral with marginal “young healthies” opting out of insurance.

So I’m sure I join the insurers currently marketing their 2026 plans in hoping that folks listen to Thom Tillis, Republican Senator from North Carolina, who said “it would probably be smart to extend current policy for a year because of the encroaching deadline and then implement changes the following year.”

Rural Health Transformation Program

BearCare, a public option (with a lot of caveats), proposed in Wyoming

The review process for the Rural Health Transformation Fund has started after all 50 states submitted their applications on time. Since the fund is only offsetting an estimated one-third of the reductions to rural health spend from H.R.1, the ambition of the program is for transformational changes to how rural care is delivered.

Skimming the applications (helpfully assembled by Chamber Hill Strategies here) and very good reporting from Inside Health Policy’s Dorthy Mills-Gregg, the big themes are what you’d expect: rural healthcare workforce development, financial stability initiatives for rural providers through value-based care arrangements, population and public health initiatives

But most interesting to me is a proposal from Wyoming called BearCare which establishes a state-run, public benefit plan which would allow individuals and businesses to buy-in at cost to what is essentially extreme catastrophic coverage. The basic shape of the program is:

The plan only covers an episode of care beginning with an “emergency anchor event” and ending with the next insurance open enrollment period

A built-in selection-bias because of the limits on coverage and screening out of people with pre-existing conditions

Payment for providers at a percentage of Medicare rates

Analysis

Some states already have quasi-public option style programs in various stages of operation like Washington, Colorado, and Nevada with Maine, Minnesota, and New Mexico evaluating their options.

In the application, Wyoming discusses the basis for the high cost of health insurance in the state:

This is due in part to the high unit prices insurers pay for medical care in Wyoming, but also due to the inclusion of the ten Essential Health Benefits (EHBs) under the Affordable Care Act —many of which go unused by generally healthy people.

There’s an interesting dynamic at play here which is that the ten Essential Health Benefits catch a lot of flak for increasing prices of insurance which is obviously true, but intuitively I would imagine the much more significant cost drivers are the unit prices in Wyoming which are about 25% higher than the national average in the case of Medicaid, and the fact that the insurance is guaranteed issue to people with pre-existing conditions.

It will be interesting to watch what happens to the entire health insurance market in Wyoming if this idea is approved. My guess would be some serious adverse selection, but we may be able to see this experiment play out in real time.

Regulatory Exposure

HTN company coverage of businesses that are regulated or otherwise impacted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

The American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) issued a policy statement endorsing alternatives to Applied Behavior Analysis like developmental relationship-based interventions (DRBI) and naturalistic developmental-behavioral interventions (NDBII). This is a tailwind for Positive Development which specializes in and has been an evangelist for DRBI. You can read our initiation of coverage report for Positive Development here.

UBS hosted their 2025 Global Healthcare Conference and Oscar, Centene, and HCA all had interesting comments on ACA and Medicaid developments:

Oscar CFO Richard Blackley shared that their price increase for 2026 marketplace plans was 28% which will put them in the lowest or second lowest price position in about 30% of their markets, an increase from 15% of their markets this year. He also shared that their book tends to skew younger and healthier meaning a change like the one the President proposed could disproportionately impact them.

Centene CEO Sarah London shared that the company was not awarded a CMS sole-source contract for Florida that they had been serving for the last 6 years. The details of the contract were fascinating to me: it’s a $5 billion contract and including a rate increase this year, they were making “very low single digit pre-tax margins” which would have declined with the contract changes with Molina taking over starting October 2026.

The discussion with hospital operator HCA included two interesting data points: first, that they are seeing a potential -1% headwind to overall volume growth if the ACA enhanced subsidies aren’t renewed with marketplace volume being one of their larger growth areas recently and second, UBS Analyst estimated an aggregate $700 million of potential EBITDA tailwinds from state directed payment programs, the program that’s getting hemmed in by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

The Hickpuff Review

The continuing resolution to fund the government that was signed into law last night includes retroactive payments and extensions for Medicare telehealth claims

Politico reported on the Healthy Opportunities Pilot in North Carolina which used “fresh food, safe housing, and transportation— social and economic factors that determine 80% of a person’s health— to improve lives of the sickest, most expensive patients” but was killed by the state legislature citing costs.

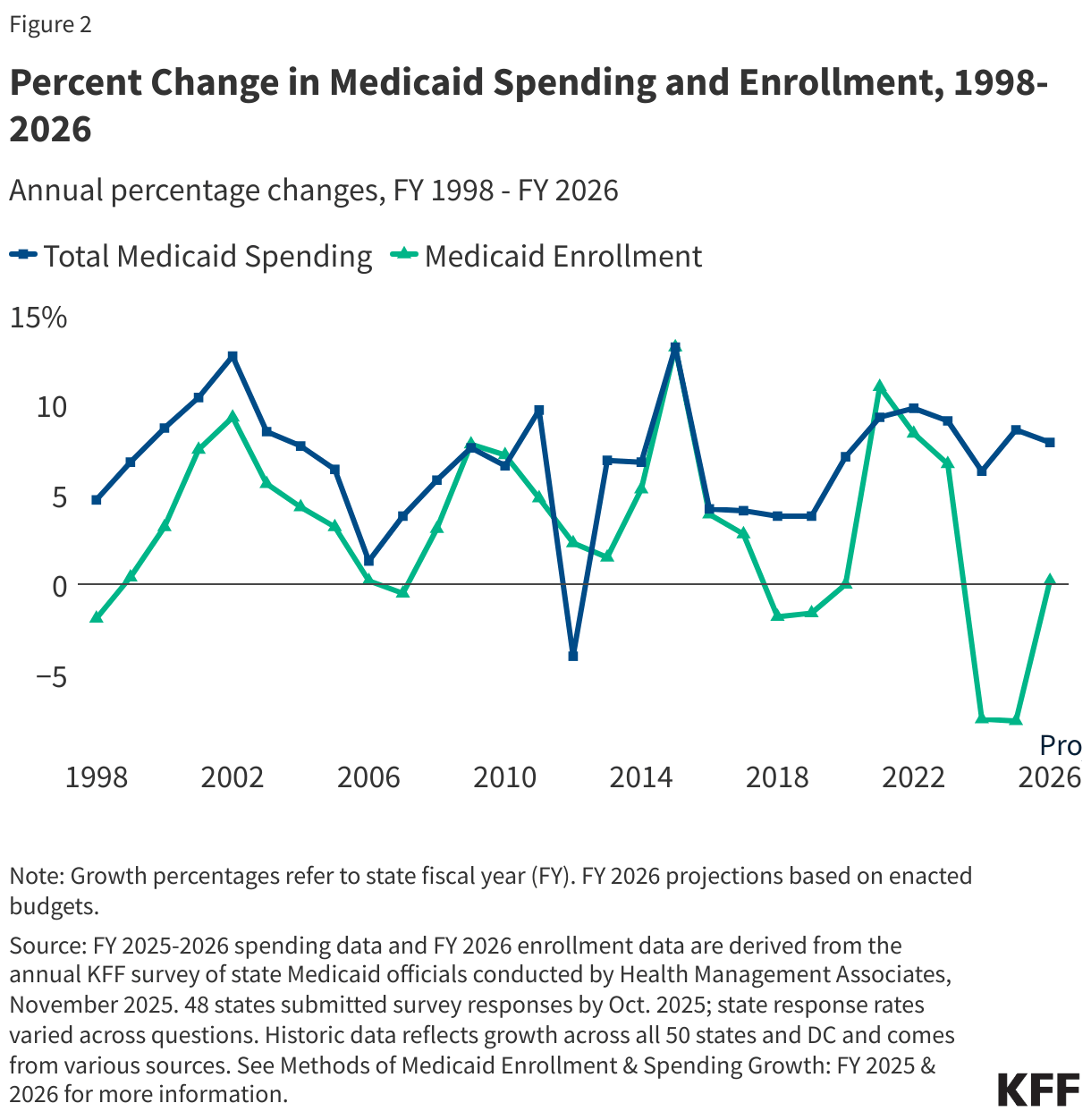

KFF released their Medicaid Enrollment & Spending Growth: FY 2025 & 2026 report which anticipates flat enrollment but an increase in spend on the order of 7.9% for 2026

Earlier this year, Montana passed a bill authorizing their Medicaid agency to explore payments for Direct Primary Care. DPCs are very much en vogue as an alternative to the status quo for primary care docs and patients. Similar to BearCare, I’ll be interested to see how this plays out in a laboratory of health policy sort of way.

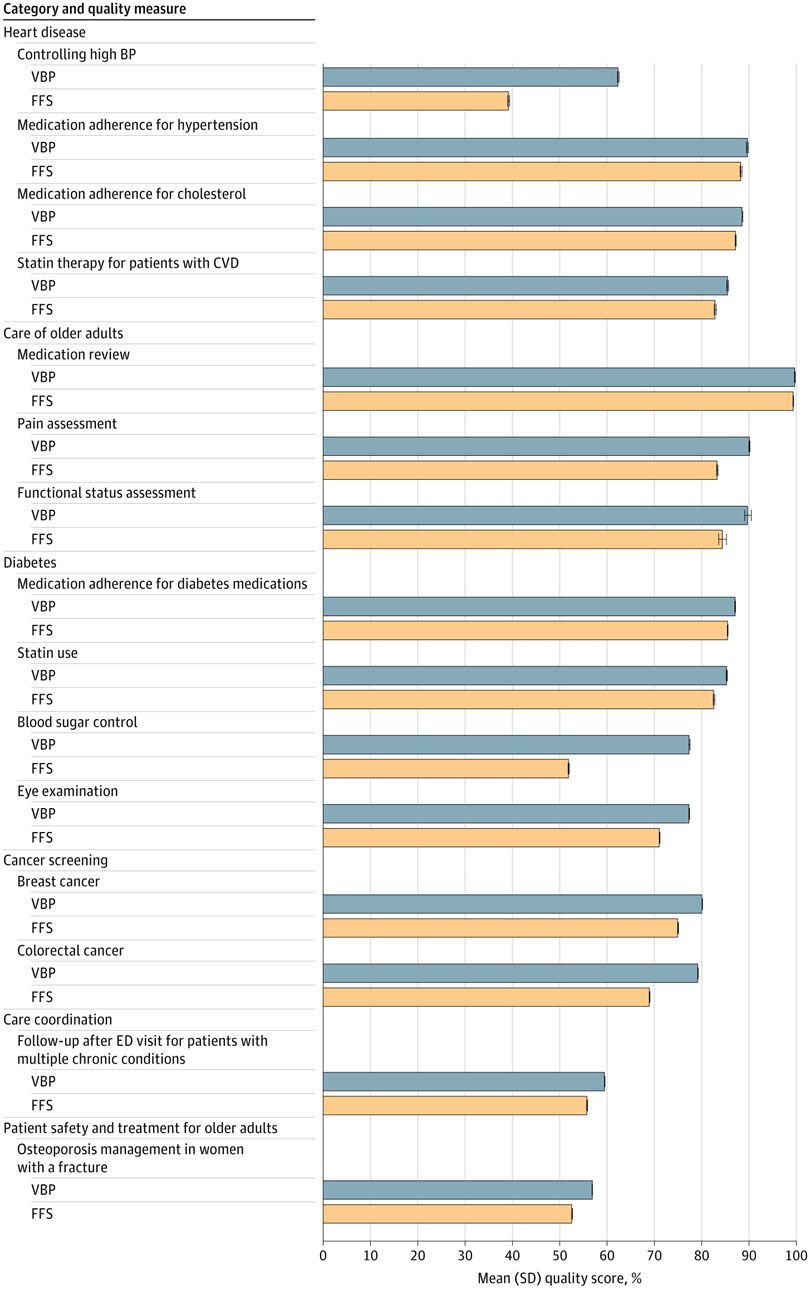

A research letter in JAMA Health Forum found comparable clinical quality measurements for FFS and VBP in all but a few measures, although Harold Miller, CEO of the Center for Health Care Quality and Payment Reform, had some pointed critiques in the comment section.

Beltz EM, Craig KJT, Xin W, et al. Clinical Quality Performance of Value-Based and Fee-for-Service Models for Medicare Advantage. JAMA Health Forum. 2025;6(9):e254002. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2025.4002

Longer form

The debate over what to do with the Affordable Care Act enhanced subsidies has been fascinating to watch as politicians, CEOs of major insurers and hospitals, and D.C. think tankers all make their arguments. As is often the case in these debates, the most and least sympathetic examples are getting a lot of play in these arguments which is certainly effective as an advocacy strategy— tugging on heartstrings or causing righteous outrage about an undeserving person getting a benefit are effective rhetorically.

For example, on their recent Q3 earnings call, Oscar CEO Mark Bertolini teed up the company’s view like this:

The average farmer making $60,000 a year now pays $75 a month for health insurance compared to $300 a month before the enhanced premium tax credits. That $225 is the difference between paying for healthcare or paying the bills. Limiting access to affordable coverage in the individual market undermines Main Street and rural America.

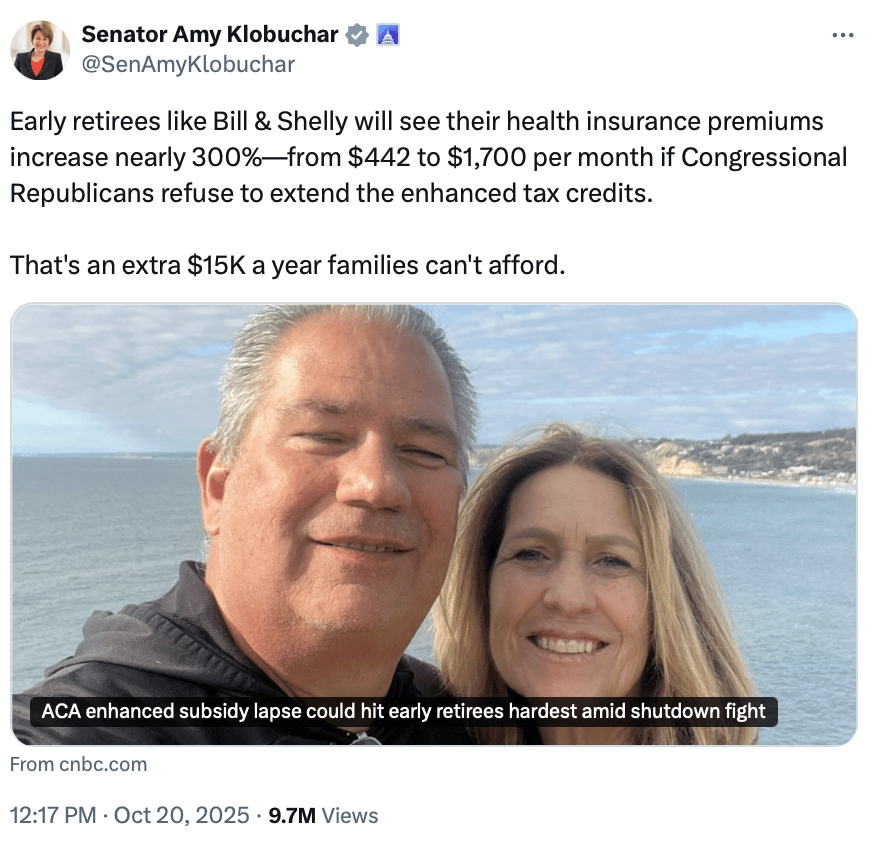

The senior senator from Minnesota, Amy Klobuchar tried to do something similar with this tweet, although despite the eye-popping price increase, perhaps early retirees with six-figure pensions weren’t the most sympathetic choice:

The Paragon Institute, firmly against renewing the subsidies, jumped on this example as proof of problems with the program:

Consider the case highlighted by U.S. Senator Amy Klobuchar: a couple in their 50s, recently retired from public employment, earning nearly $140,000 per year in combined pension income. Under the COVID credits, they received a $15,000 premium subsidy in 2025—even though they are in the top income decile. Before 2021, this couple would have received no premium tax credit (PTC) at all.

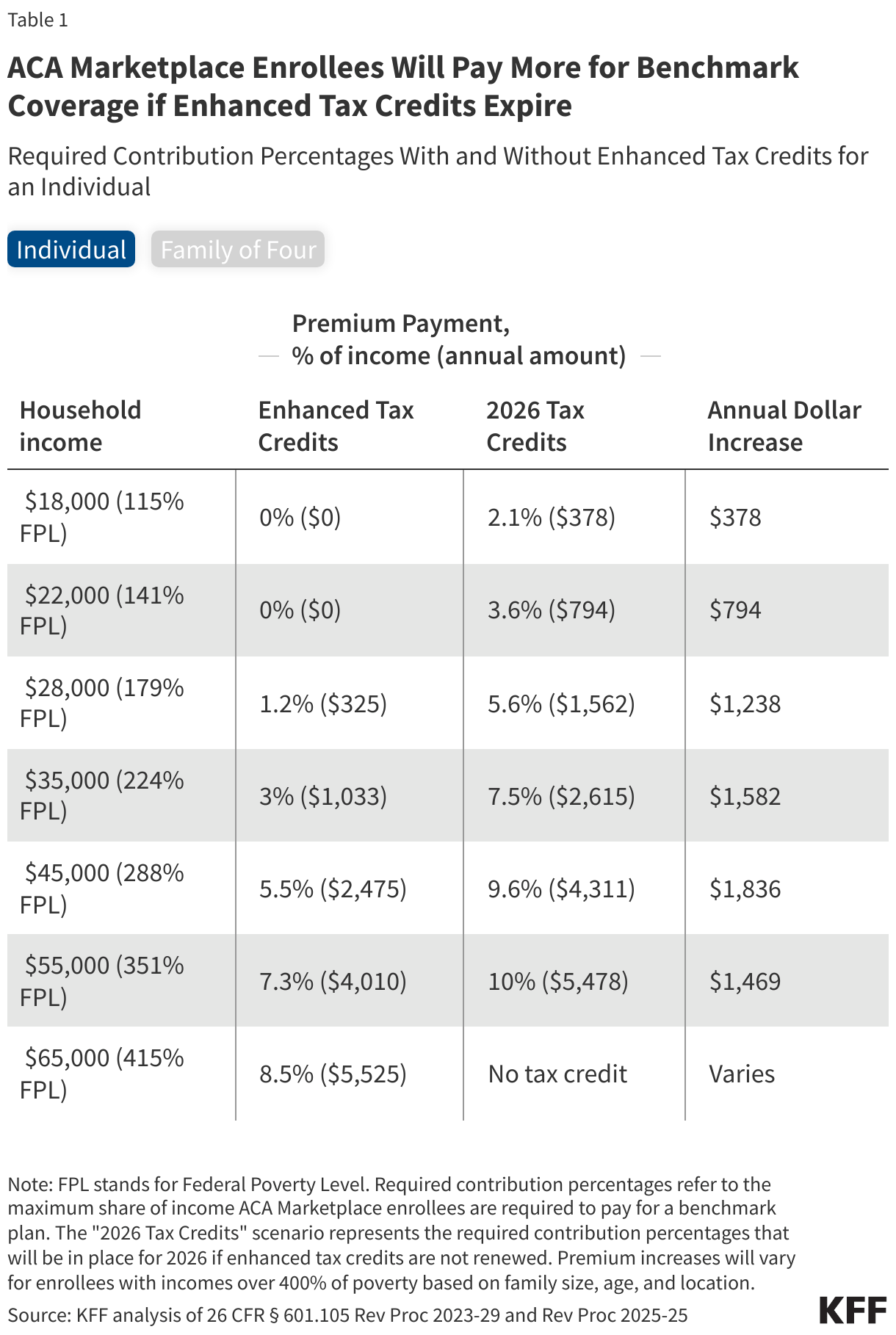

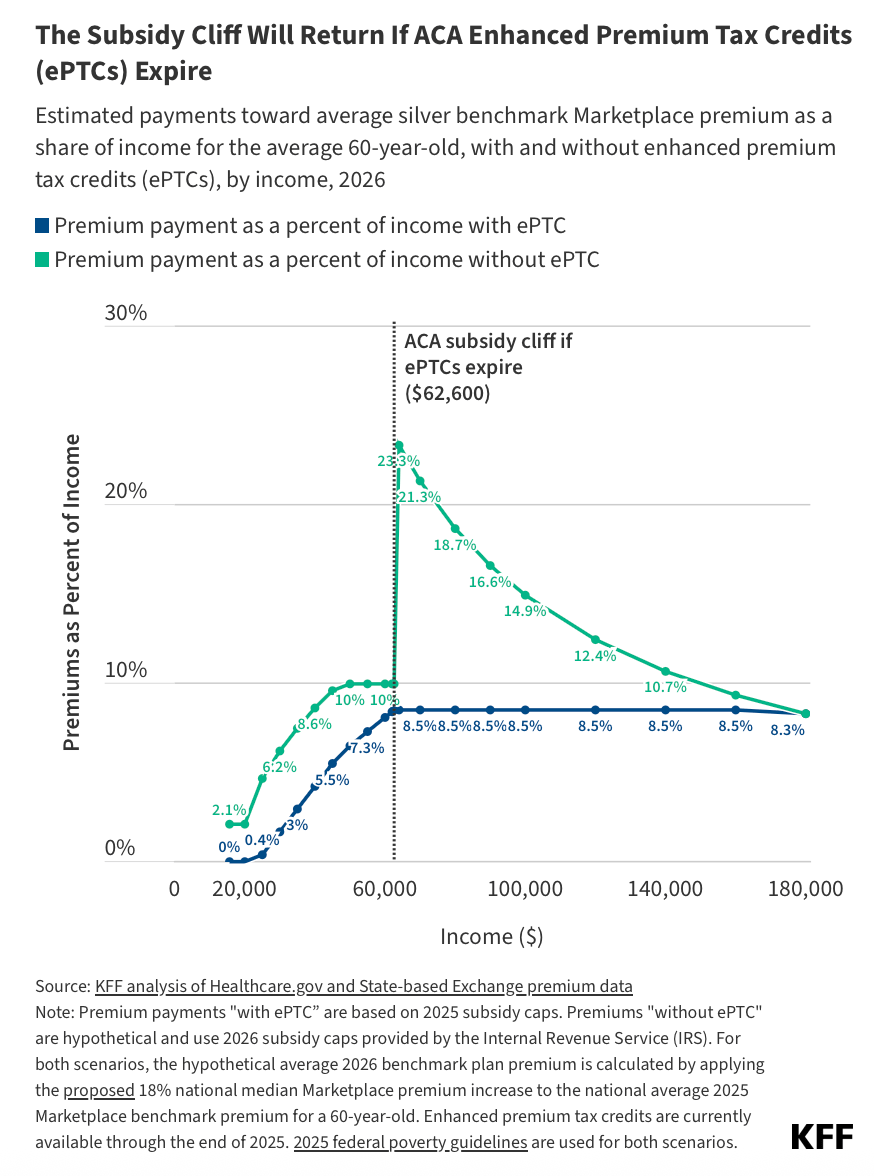

Very effective rhetorically! But, I would argue, of extremely limited use for making policy decisions. The enhanced subsidy provisions that are expiring did two main things:

Made the subsidies more generous

Eliminated the subsidy cliff so that the most that people pay for a benchmark plan is 8.5% of their MAGI

As you evaluate what should be done about these expiring provisions, it’s also useful to understand what the typical ACA marketplace purchaser looks like which from an income perspective is between 100-200% of the federal poverty line depending on whether you want the mean or median. The modal ACA purchaser is between 100-150% of the poverty line and lives in Florida.

When it comes to public policy, the optimal amount of fraud or unintended use isn’t zero. There are trade-offs between administrative burdens, access, and program uptake to consider. An asset test, for example, might negatively impact farmers who have low wages but lots of capital tied up in farm equipment and land. Going back to the subsidy cliff world would mean early retirees like Bill and Shelly wouldn’t get a subsidy, but neither would someone just over 400% of the federal poverty line whose premiums have gone up just as much. Rather than try to solve for every edge case, I think coming to a consensus around what someone should pay for insurance as a percentage of their income on the individual market is a more sensible path than trying to adjudicate whether the farmers or early retirees deserve the help or not.

1 Health care policy and financing, named after my favorite Medicaid agency