Welcome to The Library!

Welcome to The Library, a NEW

🔒 HTN members-only 🔒 weekly content series.

This is typically paid content, so if you find it valuable, upgrade your subscription to join our community to access other exclusive content.

About The Library:

Hi! Today we’re rolling out a new weekly content series for HTN community members, called The Library.

In each post, we’ll share ~1,000 words highlighting an article, story, paper, etc. that we’ve found particularly insightful on our journey seeking to better understand the business of healthcare. They’re the things we keep coming back to as foundational thinking as we dissect the healthcare trends of today.

The goal of each of these posts is to give our members a few minutes of deep thinking time each week. Some topics may be directly relevant to things you’re working on today, others less so, but our hope is you’ll find them all to be relevant learnings related to broader industry trends today.

These posts will follow a similar structure: we’ll provide a quick summary of the article, share what we learned from it, pose some questions we think are thought-provoking, and include some additional relevant links to explore more.

HTN members can check out our other Library posts. Below are links to the first six pieces we’ve done:

This Week’s Featured Article:

Why it matters:

When this article appeared in Health Affairs in Spring 2020, it was the first public conversation I recall suggesting that risk adjustment and the growth of percent-of-premium contracts for advanced primary care models in Medicare Advantage were increasing costs to the government.

As a much larger public debate has unfolded regarding the cost of Medicare Advantage, this article remains foundational for my thinking in understanding the financial impact of risk adjustment and percent-of-premium contracts on various stakeholders in Medicare Advantage.

A Brief Summary:

Back in early 2020, a team of folks who were working at Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina articulated their perspective on the key challenges holding back the broader adoption of “advanced primary care” (APC) models. If you want a quick refresher on what an APC model is, they defined APC as consisting of the following three components:

A high-touch care model focused on team-based care, smaller panel sizes,

modification of clinical workflows to incorporate data insights,

the assumption of substantial two-sided risk

As context, in 2019, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina launched an initiative supporting bringing APC practices to North Carolina. In this press release in October 2019, they discussed Iora Health, CareMore, and Cityblock’s entry to the state. Between the definition above and those companies highlighted, you can get a sense of the type of model here.

The main thrust of the article explores how policymakers might be able to make structural changes to help scale the impact of APC models. It highlighted three primary challenges with the adoption of the models back in 2020:

Challenge 1: The cost of delivering advanced primary care models limits their scope only to Medicare and Medicaid.

Challenge 2: Percent of premium arrangements cause costs to increase.

Challenge 3: These models are not structured to operate in commercial or rural environments.

While all three challenges are worth digging into, the second challenge articulated in the article is what we’ll focus on here. It highlights how risk adjustment tied to percent-of-premium contracts can increase overall costs to the government while benefitting payors, providers, and patients financially.

The article walks through the construct of a “percent-of-premium” contract, where an APC provider is paid on a medical expense target that is set as a percentage of the overall premium that the payor receives from CMS. This structure aligns financial incentives between payers, providers, and patients. And on top of the financial incentives, it helps support high-quality clinical programs for complex patient populations that need it the most.

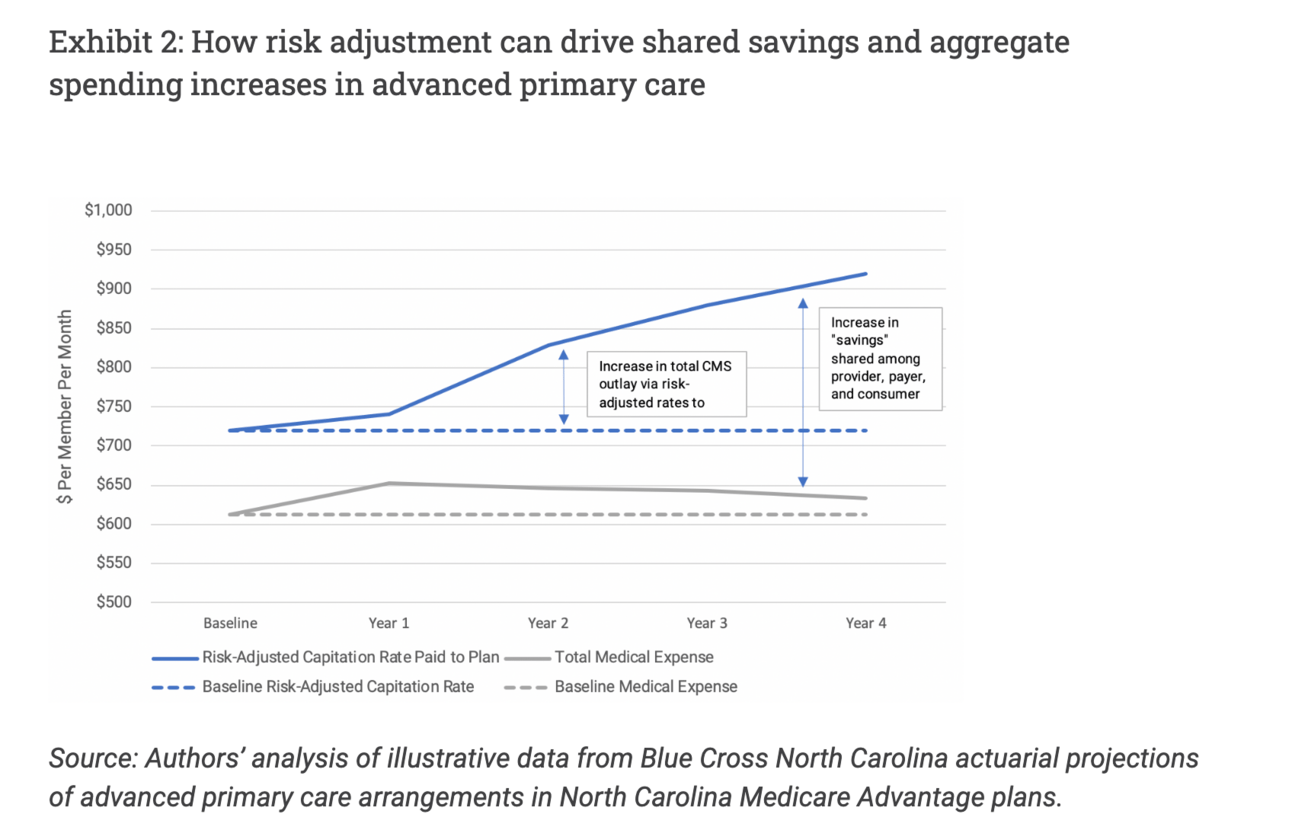

At the same time, however, the percent-of-premium construct creates a pretty clear path to increasing total cost of care for the government. Exhibits two and three below lay out the argument visually:

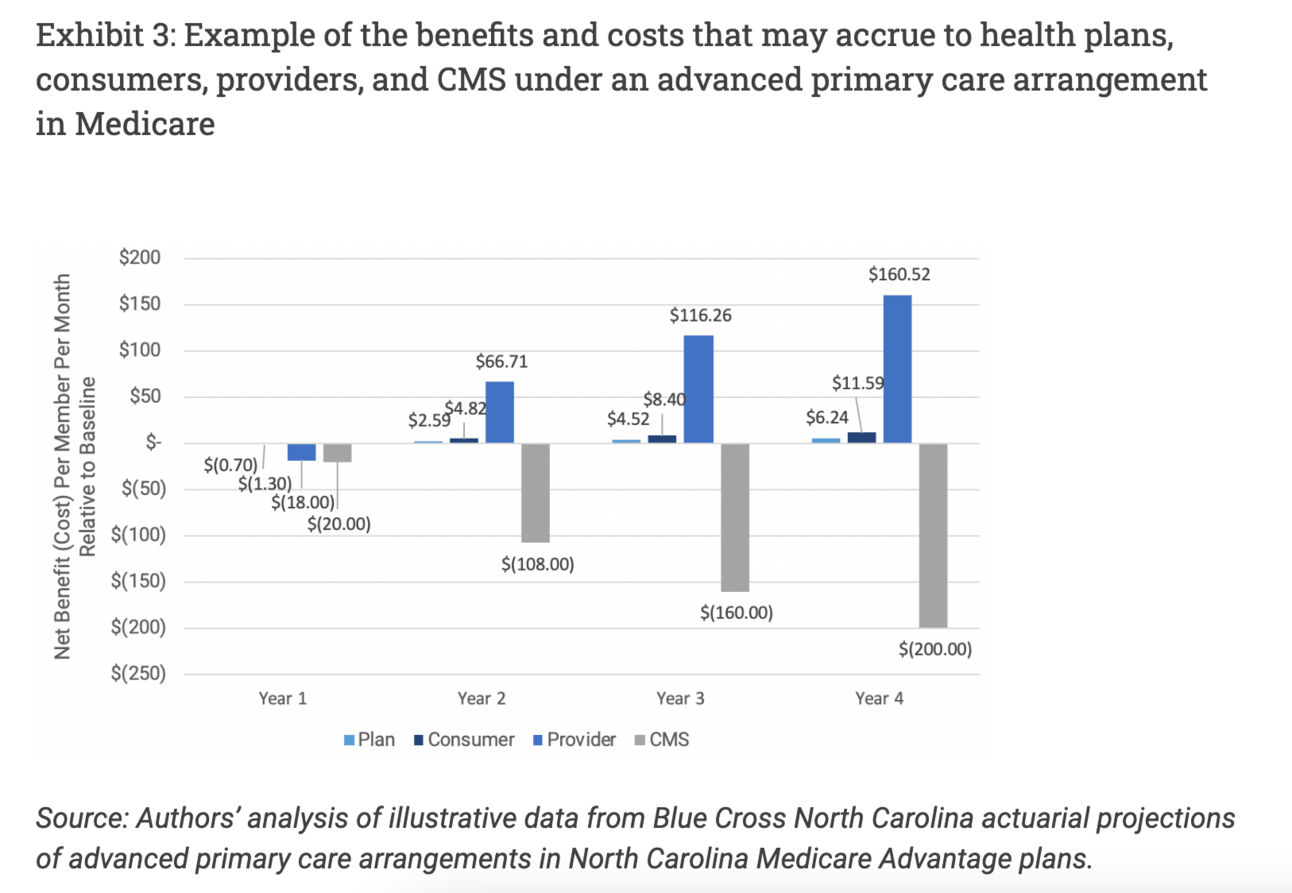

The chart above highlights the core issue that the paper points out - tying risk adjustment to a provider’s revenue creates an economic incentive to drive risk scores up over time. Below is a chart based on the same illustrative data highlighting the PMPM impacts that risk adjustment has on each stakeholder:

Over time, the plan and consumer see some benefit, but the provider captures a huge increase in shared savings given the increasing delta between the baseline medical expense and the capitated rate the payer is receiving from CMS. The paper articulates the theory of why this happens as follows:

Under current fee-for-service payment methods, providers have no incentive to record every condition of every patient. But when a managed care plan aligns its incentives with providers, such as through a percent-of-premium arrangement, providers have a strong incentive to fully document all patient conditions. We believe this effect would occur across much of the nation, and we estimate that complete and accurate coding—documentation that is comprehensive but does not run afoul of regulations—could increase patient risk scores in MA plans by 10–25 percent, depending on the market, from current levels over four years.

The paper goes on to suggest some ways policymakers could potentially mitigate the issues raised above. That included the radical idea of getting rid of risk adjustment payments altogether (noting that would raise a new set of thorny issues to manage).

My Key Learnings:

The charts highlighted above were the first time I saw a public conversation about how risk adjustment in the Medicare Advantage market could be driving benefits for payers, providers, and patients, all while ultimately costing the government more.

The charts in the article are pure health tech nerd gold. Here you have a team from Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina pointing to an actuarial analysis with illustrative data to show how costs adjust over time. Remember that BCBS NC at the time had invested heavily in bringing advanced primary care models into the state, including Iora Health, CareMore, and Cityblock.

I find the case above to be helpful grounding in the massive debate that has emerged over the last several years over whether Medicare Advantage saves the government money. It’s been a confusing debate to follow, with various constituents seemingly making the case that aligns with their financial interests.

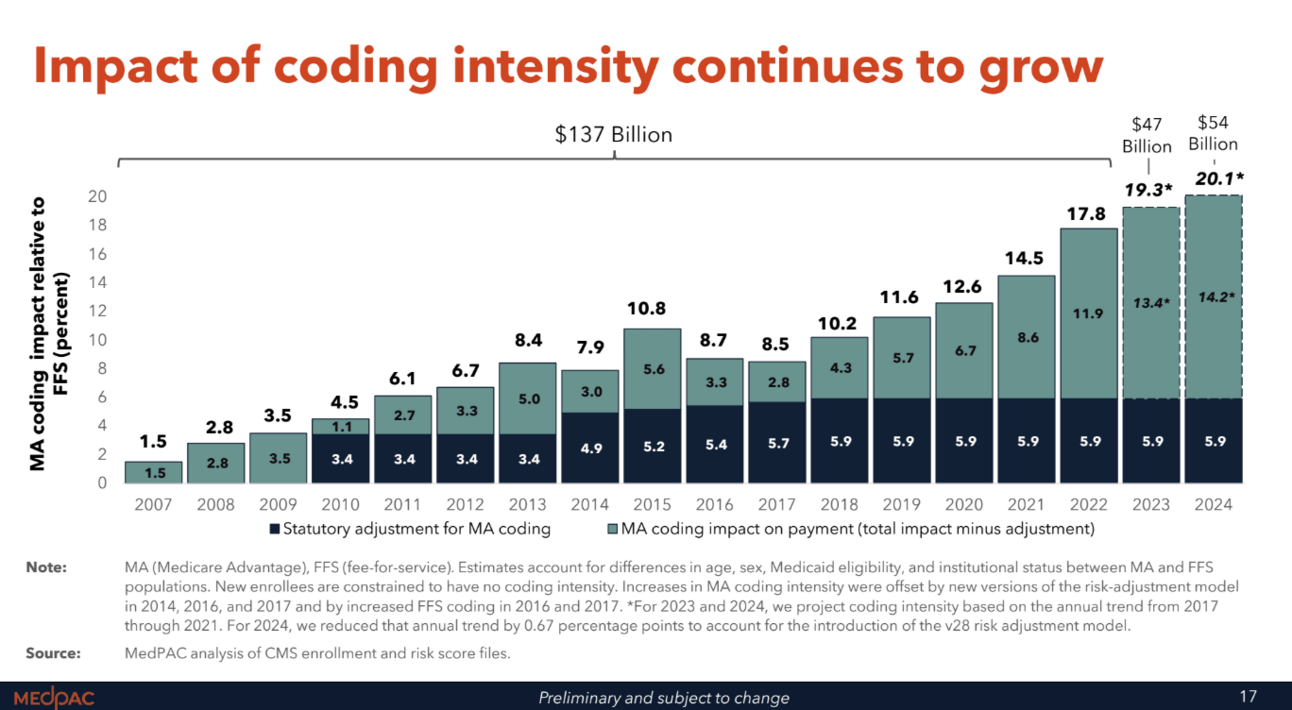

For me, the logic outlined in the charts above and detailed in the article makes a compelling case showing why the combination of risk adjustment and percent-of-premium contracts should likely lead to the Medicare Advantage program increasing government spending while creating savings for payers, providers, and patients. The fact that MedPAC and other organizations are pointing to those overpayments increasing over the last few years seems confirmatory of that theory. It is striking to see the article above predicting risk score growth by 10% - 25%, and then compare that to this MedPAC chart from January 2024 on the impact of coding:

Even beyond the financial incentives and how they’ve played out the logic laid out in the article for why this is happening makes a ton of sense to me. In a fee-for-service world, there is no real financial incentive for providers to code accurately and completely. Yet in this percent-of-premium world, it has a massive financial impact on these providers. So it makes sense that they’d prioritize documenting these codes in a way that hasn’t been done elsewhere. The logical result is that risk scores would increase, and the financial impact would generally follow what the article articulated. The MedPAC data seems to confirm this has happened in subsequent years.

It’s worth bearing in mind that the challenges posed by the article do not negate the benefits of advanced primary care models. The article itself is about how to overcome these challenges to scale these APC models given the benefits they can offer. But it is important to understand the details of how money flows in these sorts of arrangements because ultimately these financial incentives are what drive behaviors.

Discussion Questions

Question 1: How much do you think this percent-of-premium and risk score dynamic has played into the desire for payers to vertically integrate in the Medicare Advantage market over the last 5 years? What happens in this space if the government decides to stop footing the bill for increased costs?

Question 2: If you’re looking at an advanced primary care model from the outside (i.e. a potential investor, partner, or employee) and trying to evaluate what impact it has on reducing total cost of care versus increasing risk adjustment revenue, how do you think you’d attempt to discern the difference?

Question 3: The discussion above is very focused on the costs of these models and whether or not they generate savings for various constituents. To what extent do you think advanced primary care models are worth adopting even if they don’t save money in aggregate? How would you evaluate this?

The Cost Equation of Primary Care Models. This 2017 post outlined my learnings on how primary care models can potentially drive savings in a commercial market and the challenges associated with it.

One Medical + Collective Health Study. This study in JAMA Open Network suggests One Medical’s primary care model resulted in 45% lower costs for an employer, somewhat opposite to the case made in the article above about the ability to drive down costs in employer models.

The MA Money Machine. The article(s) that started the Medicare Advantage risk adjustment debate nationally. It’s worth reading to understand the various provider coding deals and the impact those have on costs. [Part 1 | Part 2]