I’ve been thinking a lot about the physician supply shortage in the United States lately— a seemingly intractable problem that cuts across urban and rural areas and is especially acute among primary care and along with a subset of specialties like psychiatry and, increasingly, OB-GYN.

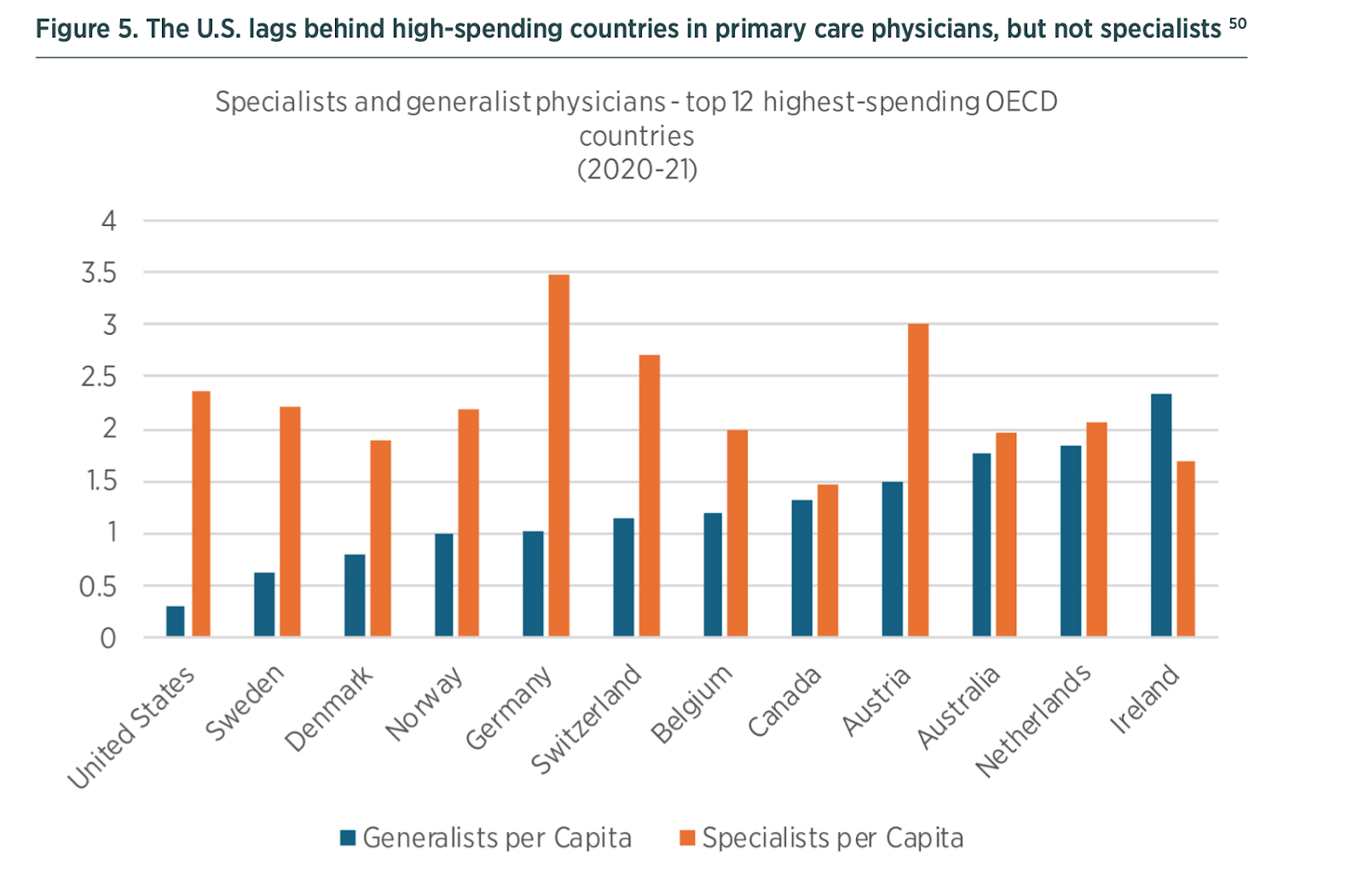

In primary care, for example, the U.S. lags our peer countries in generalists per capita by to a staggering degree:

Chart from the Niskanen Center on healthcare abundance

An appealing answer to this problem in an era of Abundance discourse is to just train more doctors. For mostly not very good reasons, this hasn't happened yet and is unlikely to materialize on a short enough timeline to alleviate the problem.

A compelling alternative to the status quo1 is increasing the autonomy and scope of practice for nurse practitioners - nurses with advanced degrees and training, often referred to simply as NPs. More than half of states allow nurse practitioners a full scope of practice, but it’s still a regulatory patchwork state-by-state with varied collaboration requirements and confusing practice ownership rules which are dampening the ability of NPs to meet the pent-up demand the lack of physicians has created.

Unlocking this supply seems like an obvious solution to an increasingly pressing challenge, so I was curious to learn where the bottlenecks are. I chatted with Meghan Jewitt, CEO of Prax Health, who is building a “business in a box” that helps nurse practitioners navigate the regulatory and administrative challenges of opening and operating their own clinics and she was gracious enough to talk me through the main constraints. I’ve summarized our discussion below and quoted her directly in places.

(1) The state-by-state scope of practice patchwork

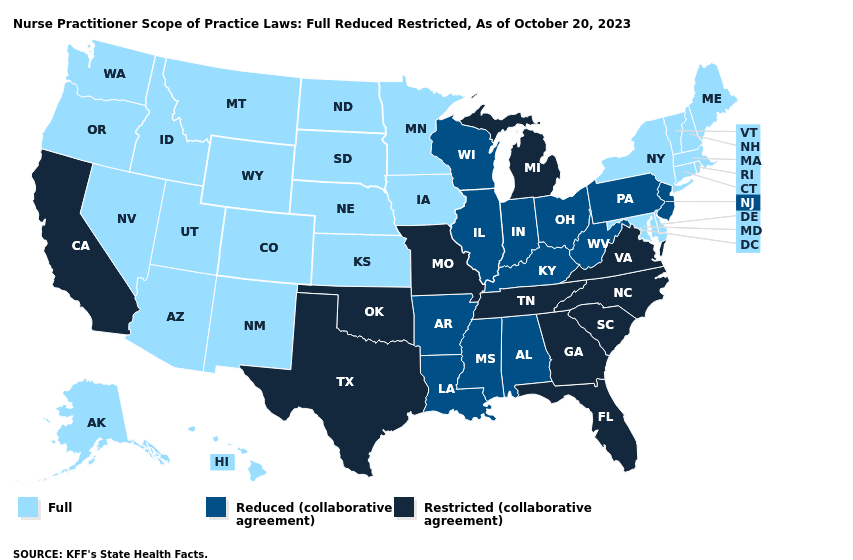

States get to decide what a nurse practitioner’s “scope of practice” is and when you ask 50 states the same question, you’re likely to get a wide variety of answers. KFF helpfully buckets states into three categories:

Full scope of practice

Reduced scope of practice, requires a collaborative practice agreement with a doctor

Restricted scope of practice, requires of a collaborative practice agreement with a doctor

Practically, Meghan walked me through what this means, “At a high level, these three categories describe the degree of autonomy that an NP has state-by-state to evaluate, diagnose, prescribe, order labs, and coordinate patient care. Full practice authority states are the most straightforward and no physician supervision is (generally) required. Whereas reduced states and restricted states require a supervising physician to be in place in some capacity. The AANP has a great resource page on the state environment for NPs.”

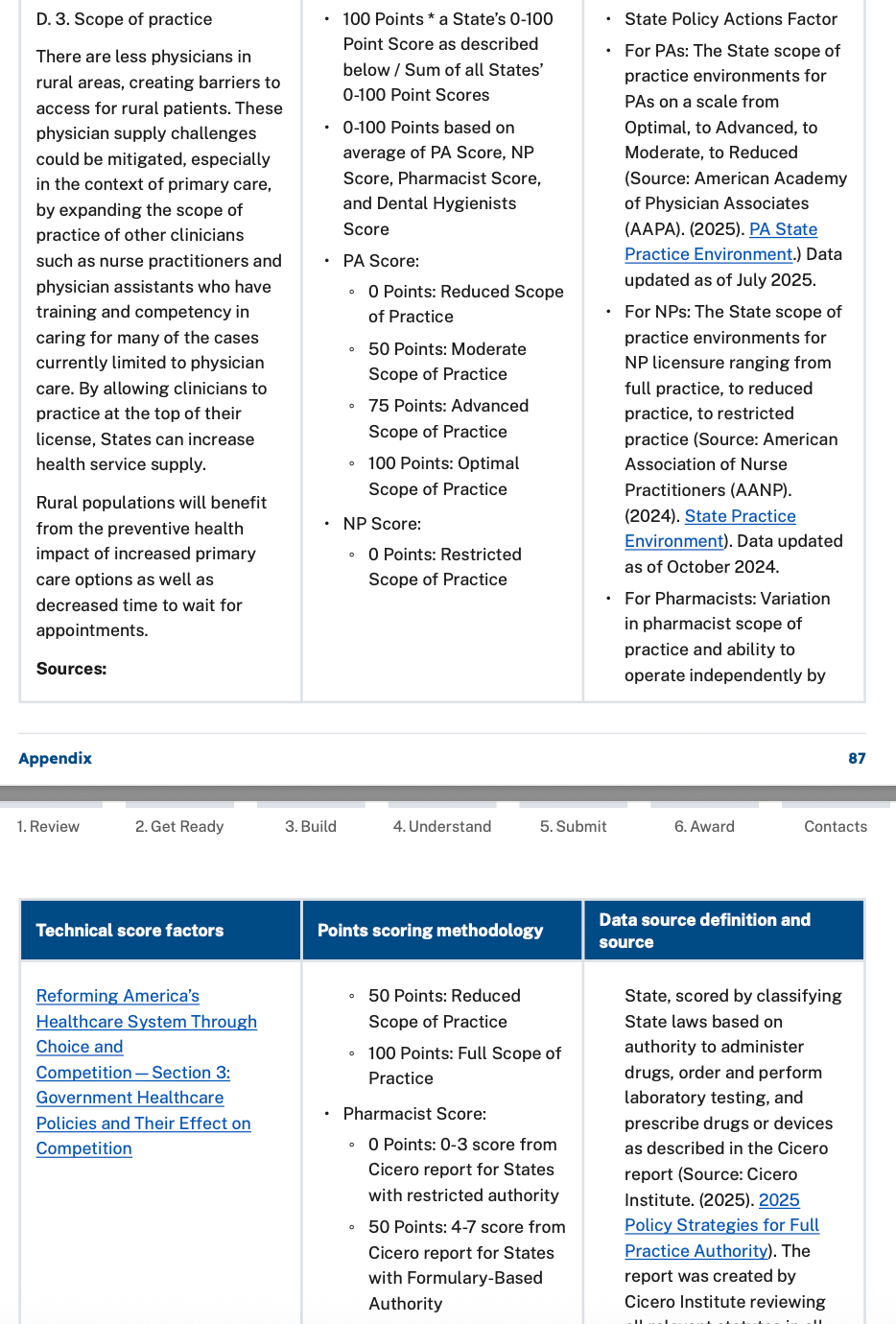

This sort of patchwork approach to regulation isn’t unique to NPs— Physician Assistants face similar issues with their scope of practice changing as they cross state lines. More broadly, state by state licensing for NPs, PAs, and physicians adds friction to mobility for providers and limits providers ability to practice out of state. Both of these issues, licensure compacts and scope of practice, are part of the technical score factors for scoring state’s applications for the $50 billion rural health transformation program. Each of these criteria is worth 1.75% of the $25 billion in RHTP funding, so a state that isn’t an interstate compact member and doesn’t have expansive scope of practice rules for NPs (along with PAs, Pharmacists, and Dental Hygienists) would stand to lose out on their share of the $875 million dollars allocated based on these criteria.

(2) Collaborative practices agreements as an expensive bottle neck

As the American Medical Association is quick to point out, there are significant differences in the scope and scale of training between medical school plus residency and the training a nurse practitioner receives. In principle, a collaborative practice agreement is meant to mitigate these concerns by having a collaborating physician in the loop.

Meghan explained that these collaborative practice agreements vary state-by-state ranging from, “a simple collaborative practice document to complex chart review and geographic requirements.” To give me a sense of the state-by-state variation, she explained that, “While some states have a simple agreement that is signed once and recurs indefinitely, 4 states require MDs to be in same building as NPs to meet supervision requirements, 2 states have geographic radius requirements (e.g. in Georgia an MD must be physically based 50 miles from the NP), and 12 states have some version of chart reviews.”

The collaborative practice agreement situation has created something of a cottage industry for physicians with “quite a few businesses that specialize in helping NPs to find collaborating physician ‘matches’. Anecdotally, most NPs we speak with find the supervision requirements to be frustrating as they add expense and often not a lot of value.”

What was most surprising to me about these collaborative practice agreements was the economics of it for NPs and physicians: “it is not uncommon to see a collaborating physician supervise 50 or even 100 NP collaborators, often earning $500-$1,000 per APRN per month.” At the high-end, a collaborating physician could be earnings $100,000 a month in fees from nurse practitioners.

There’s been a paucity of good research on the agreements and their impacts on clinical outcomes and access, but Meghan said Prax would be interested in partnering with any researchers wanting to study the question.

(3) Corporate Practice of Medicine and Physician Ownership of NP Practices

In addition to collaborative practice agreements, there’s also a pervasive belief that practices set up by nurse practitioners need to be majority-owned by physicians, which really limits the risk premium for nurse practitioners calculating whether setting out on their own makes sense.

Meghan and the Prax Team work closely with McDermott and other leading healthcare counsel, and she explained that this just isn’t the case: “Nurse practitioners can absolutely own 100% of their practices even in CPOM states. The reason is that NPs are actually regulated by the Board of Nursing in every U.S. state. If a practice is set up under the Board of Nursing (as a PC, PLLC, etc.), an NP can wholly own that entity. The confusion comes if an NP sets up an entity under the Board of Medicine in a CPOM state, then a physician must own at least 51%. As an example, in a CPOM state (like California), if you are a licensed Nurse Practitioner, you can set up a nursing practice under the Board of Nursing, and those CPOM rules don’t apply — and you can own 100% of your practice.”

A solvable problem just by the numbers

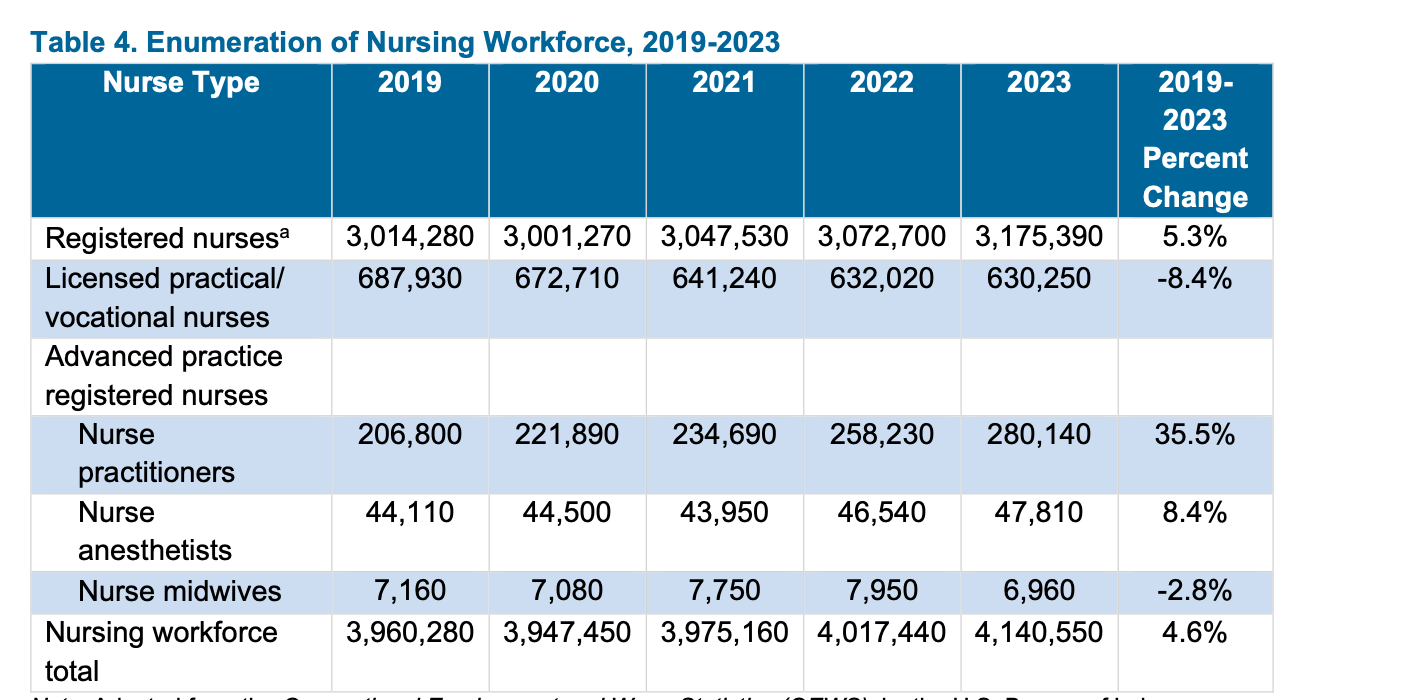

The latest statistics from HRSA show a promising 35.5% rise in nurse practitioners between 2019 and 2023 with over 334k advanced practice registered nurses in the United States at the time of the study, and a large and growing “bench” of registered nurses who could be trained into the role.

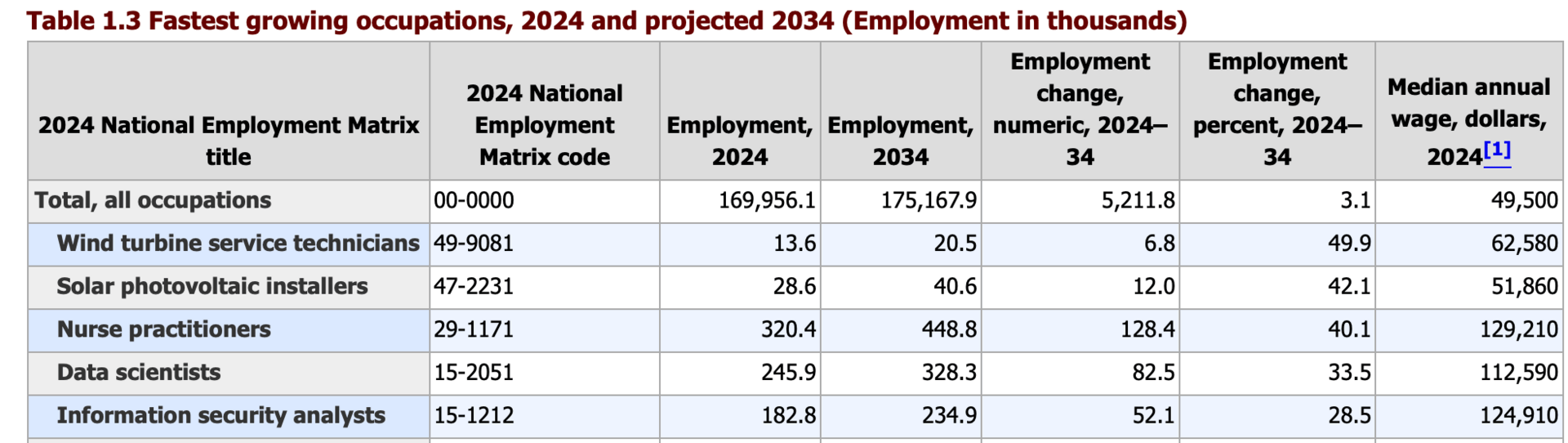

In fact, nurse practitioners are the number three on BLS’ list of fastest growing professions, and the one with the highest median annual wage:

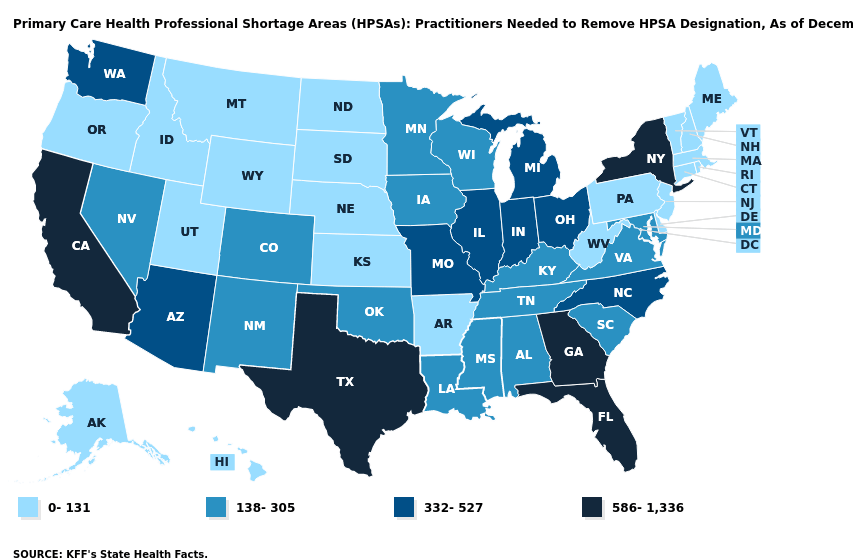

When I look at this map of the Primary Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and how many practitioners are needed to resolve the shortage, and compare it to the trained NPs and potential NPs in the table above, the shortage starts to seem like a solvable problem.

A special thanks again to Meghan for talking me through this. Prax Health is doing really interesting work making it easier for NPs to open their own practices, and combined with some policy interventions, it seems like a promising path towards shorter wait times for patients.

1 Questions about comparative quality and efficacy between physicians and NPs are contentious and ultimately very hard to answer. A brief scan of the literature indicates similar outcomes to physicians in some settings, though you’ll note this list is curated by the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, while a working paper in NBER found “that, on average, NPs use more resources and achieve less favorable patient outcomes than physicians” albeit with “larger productivity variation exists within each profession, leading to substantial overlap between the productivity distributions of the two professions; NPs perform better than physicians in 38 percent of random pairs.” I’m setting these questions aside as I think about increasing provider supply, because in the case of physician shortages, the choice isn’t often between an NP or a physician, but between an NP and no provider at all.